Advertisement

The best predictor of whether your boat will survive a hurricane is where it's kept. The most important consideration should be location.

Boats that are hauled out are far less likely to be damaged during a storm than those left in the water. Using straps is effective at keeping boats from toppling over or floating away.

Going back as far as Hurricane Alicia in 1983, our BoatUS Hurricane Catastrophe Team (CAT) professionals have spent thousands of hours working to identify and recover damaged boats. They've seen firsthand what works and what doesn't when a boat is prepared for a hurricane.

When asked where CAT team members would take their own boats if a hurricane warning were posted, most agreed: They'd have it hauled ashore. For many boat owners and marinas, hauling boats is the foundation of their hurricane plan. Some farsighted marinas and yacht clubs have evacuation plans to pull as many boats out of the water as possible whenever a storm is approaching and secure the rest in the largest available slips.

Securing A Boat Ashore

Some types of boats must be pulled if they're to have any chance of surviving. For instance, smaller open boats and high-performance powerboats with low freeboard will almost always be overcome by waves, spray, and rain. This is true even if the boats have self-bailing cockpits. Fortunately, most of these boats can be placed on trailers and transported inland.

Boats ashore should be stored well above the anticipated storm surge, but even when boats are tipped off jackstands and cradles by rising water, the damage they sustain in a storm tends to be much less severe than the damage to boats left in the water. Windage is also a consideration. If nothing else, reduce windage as much as possible (see Find And Fix Potential Breaking Points). Make sure your boat has extra jackstands, at least three or four on each side for boats under 30 feet, and five or six for larger boats. Jackstands must be supported by plywood and chained together to stop them from spreading. To reduce windage, some ambitious boat owners on the Gulf Coast have dug holes for their sailboat keels so the boats present less windage. Smaller sailboats are sometimes laid on their sides.

One technique that has proven very effective involves strapping boats down to eyes embedded in concrete. At least two marinas in Florida and one in Puerto Rico have used straps with excellent results. One of the Florida marinas strapped the boats to eyes embedded in its concrete storage lot. The other Florida marina and the one in Puerto Rico built heavy concrete runners (similar to long, narrow concrete deadweight moorings) beneath the boats to anchor the straps. (Straps made from polyester work better than nylon, which has more stretch). Even when the wind has been on the beam and water has come into the storage area, the straps held and boats stayed upright. An alternative tried at other marinas has been to use earth augers screwed into the ground to secure the straps. Results with the latter technique have been mixed; some have held while others have been pulled out. All things considered, any attempt to anchor a boat on shore is worth the effort.

Tip

Securing A Boat In The Water

Any boat in the water should be secured in a "hurricane hole," which means a snug harbor protected on all sides from open fetch and unrestricted storm surge. (Don't even think about riding out the storm at sea unless you're the skipper of an aircraft carrier!) The trick is deciding which harbors will still be safer if a hurricane comes ashore and which ones will be vulnerable. Storm surge — high water — is a major consideration. A storm surge of 10 feet or more is common in a hurricane, so a seawall or sandy spit that normally protects a harbor may not offer enough protection in a hurricane.

Another consideration is rocks. Crowded, rock-strewn harbors are picturesque but not a good place to keep your boat in a storm, particularly if your boat breaks loose. If you plan to anchor, choose your bottom well for holding your type of boat with your type of anchors. Also, water can sometimes be blown out of the harbor, leaving boats stranded briefly. If this happens, your boat would rather settle onto anything but rocks.

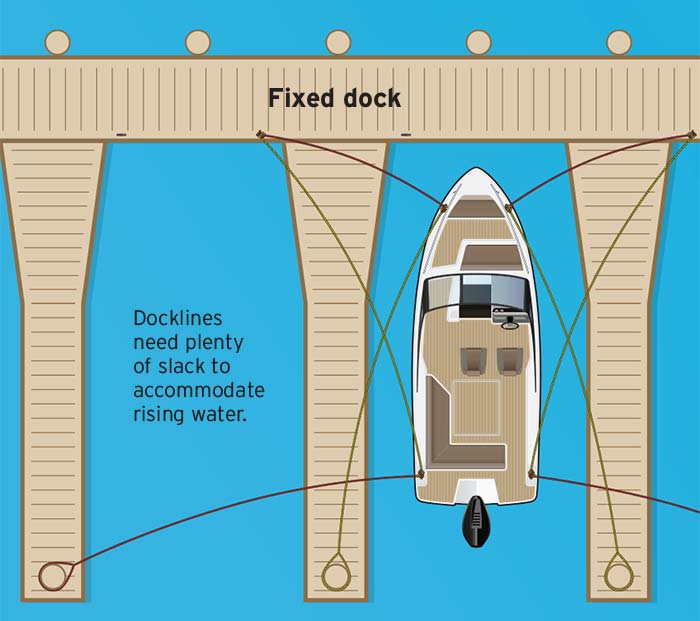

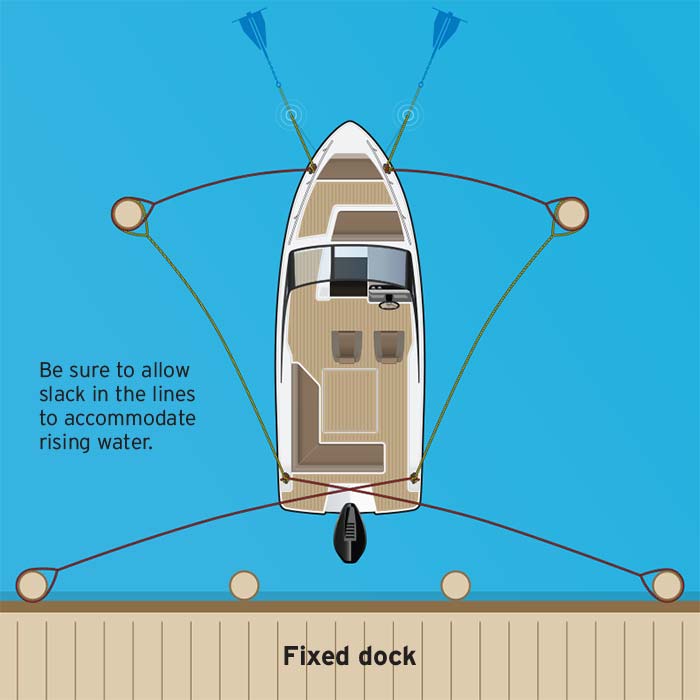

At A Fixed Dock

Members of our BoatUS CAT Team estimate that as many as 50 percent of the boats damaged at fixed docks during hurricanes could've been saved by using better docklines — lines that are longer, larger, arranged better, and protected against chafing. If you decide to leave your boat at a dock, you'll need to devise a docking plan that's liable to be far different than your normal docking arrangement. By the time preparations are completed, your boat should resemble a spider suspended in the center of a large web. This web will allow the boat to rise on the surge, be bounced around by the storm, and still remain in position.

Lines should be extra long to allow for surge. Double lines up where possible. (Illustration: Erich Stevens)

Take a look at your boat slip and its relation to the rest of the harbor. For most boats, you'll want to arrange the bow toward open water or, lacking that, toward the least protected direction. This reduces windage and keeps the strongest part of the boat — the bow — facing the storm. If your boat has a swim platform, especially one that is integral to the hull, you'll need to take extra care that the platform can't strike anything. Boats have been sunk when their platforms were bashed against a bulkhead.

Next, look for pilings, dock cleats, trees — anything sturdy — that could be used for securing docklines. Avoid cleats that do not have sufficient backing. Just bolting them through dock planks will probably not suffice. Not all pilings are sturdy, though. Old wood pilings that are badly deteriorated should obviously not be relied on in a storm. The same is true of older concrete pilings, which seem to be more susceptible to snapping in half (and sometimes landing on boats) than their more pliant wood counterparts. Many of the boats that were wrecked in Hurricane Charley had been secured to concrete pilings that couldn't stand up to the lateral stress and twisting. And at least one marina in Pensacola had almost all its concrete pilings fail. All things being equal, wood is a better choice unless the concrete pilings are relatively new.

If you don't have a slip, tie extra-long lines to pilings or cleats to allow for the surge, which could be 10 feet or more. Use anchors or long spring lines to keep the boat from striking the dock. (Illustration: Erick Stevens)

Lines should also be a larger diameter to resist chafe and excessive stretching. On most cases, you should use ½-inch line for boats up to 25 feet; 5/8-inch line for boats 25 feet to 34 feet, and 3/4- to 1-inch lines for larger boats. Chafe protectors (see Find And Fix Potential Breaking Points) must be on any portion of the line that could be chafed by chocks, pulpits, pilings, and so on. To secure lines to hard-to-reach outer pilings, put the eye on the piling so that lines can be adjusted from the boat. For other lines, put the eye on the boat to allow for final adjustment from the dock.

At A Floating Dock

Because they rise with the surge, floating docks allow boats to be secured more readily than boats at fixed docks. There's no need to run lines to distant pilings because the boats and docks rise in tandem. Floating docks only offer protection from the surge, however, if — a HUGE if — the pilings are tall enough to accommodate the surge. In almost every major hurricane, there have been instances where the surge has lifted floating docks up and over pilings. When that happens, the docks and boats, still tied together, are usually washed ashore in battered clumps.

If you plan to leave your boat at a floating dock, it's critical that you measure the height of the pilings. Will they remain above the predicted storm surge? Pilings that are only 6 or 7 feet above the normal high tide probably won't be safe. When floating docks have been rebuilt after hurricanes, the new pilings have almost always been much taller, up to 18 feet tall, and are far less likely to be overcome by surge than the 6- to 8-foot pilings that they replaced. Taller pilings are much more "stormproof."

Canals, Rivers, and Waterways

Whenever canals, rivers, or waterways are available, they serve as shelters — hurricane holes — and may offer an alternative to crowded harbors and marinas if you have no alternative. Your mooring arrangement will depend on the nature of the hurricane hole. In a narrow residential canal, a boat should be secured in the center with several sturdy lines ashore (the "spider web") to both sides of the canal. This technique was common to most of the boats in canals that survived recent hurricanes. Conversely, boats that were left at docks without the benefit of lines to both sides of the canal didn't fare any better than boats at marina docks.

Advertisement

The boat should be facing the canal's entrance and be as far back from open water as possible. Besides sheltering the boat, being away from the entrance should help with another consideration, which is the need to maintain a navigable waterway. Securing boats in residential canals is possible only if you make arrangements with the homeowners whose trees and pilings you'll be using to secure your boat. This can be difficult if your boat isn't normally moored in the canal. If your boat is already in the canal, getting other homeowners involved in planning for a hurricane increases the chances that your boat (and theirs) will survive. This is important because all it takes to wreak havoc in a narrow canal is one or two neglected boats coming loose.

In wider canals and waterways, boats should be secured using a combination of anchors and lines tied to trees ashore. More lines and anchors are always better. Try to find a spot that is well away from open water and that has tall banks, sturdy trees, and few homes. Moor your boat away from the main channel. Other considerations: A hurricane hole that ordinarily takes an hour to reach may take two hours or more to reach when winds and seas are building, bridges will likely not open as frequently once a hurricane warning has been posted, the bridges may be locked down for evacuation by vehicle, or the hurricane hole may be crowded when you get there. Plan on moving your boat early.

At A Mooring Or At Anchor

Mooring in a sheltered location can also be a good alternative to exposed harbors and/or crowded marinas. A boat on a mooring can swing to face the wind, which reduces windage, and can’t be slammed into a dock unless the mooring or anchor drags. The first question, then, is, will your mooring hold? As a result of numerous moorings being dragged during hurricanes and northeasters, a study by the BoatUS Foundation, Cruising World magazine, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that a 500- pound mushroom buried in mud could be pulled out with 1,200 pounds of pull (supplied by a 900-hp tug); an 8,000- pound deadweight (concrete) anchor could be pulled out with 4,000 pounds of pull. A helix mooring, however, could not be pulled out by the tug, and the strain gauge recorded 12,000 pounds of pull — its maximum — before a shackle burst apart from the strain. Scope in each case was slightly less than 3:1.

Helix moorings were found to hold better than other types of moorings, withstanding more than 12,000 pounds of strain.

The holding power of a mushroom or deadweight mooring anchor can be increased by extending the pennant's scope, which has as much to do with the holding power of a mooring as it does the anchor itself. (Additional scope, while always advantageous, appears to be less critical with helix anchors.) Studies have found that when the angle of pull increases to 25 degrees, a mooring's holding power begins to weaken precipitously. So in shallow harbors, where a scope of 3:1 can be had with, say, 20 to 30 feet of chain, the advantage of scope is all but eliminated in a storm by a combination of a large tidal surge and the high, pumping motion of waves. Note that in a crowded harbor, scope must be increased uniformly on all boats.

Finally, when was the last time your mooring's chain was inspected? Chain that is marginal in the spring won't be sufficiently strong at summer's end to stand up to a hurricane. A harbormaster should know how long your chain has been in use and whether its condition could be iffy. If you have any doubts about your mooring, the chances of it failing can be reduced significantly by using one or two additional storm anchors to enhance its holding power and to decrease the room your boat will need to swing.

As with moorings, conventional storm anchors rely on scope — at least 10:1 if possible — to increase holding power. Heavy, oversize chain is also recommended; 50/50 is probably the optimum chain-to-line ratio. In theory, a riding weight, or sentinel, placed at the chain/ line juncture will lower the angle of pull on the anchor and reduce jerking and strain on the boat. During a hurricane, however, its value will be diminished by the extreme pressure of wind and waves, and a sentinel (and the weight of the chain) should never be relied on to compensate for lack of scope. To absorb shock, an all-chain rode must have a snubber (usually nylon line) that is 30 percent of the rode's length. Without the nylon line, the surging waves and intense gusts are much more likely to yank the anchor out of the bottom.

BoatUS CAT team members have consistently found that boats using single working anchors were much more likely to have been washed ashore. Conversely, more and larger anchors (suited for the type of bottom) increased a boat's chances of staying put. One CAT team member says he's impressed with the number of boats that ride out storms successfully using two large anchors with lines set 90 degrees apart. With this technique, one rode should be slightly longer than the other so they won't become tangled should they drag. Even more staying power can be had using the tandem anchoring technique — backing each anchor with a second anchor. Using tandem anchors allows the first anchor to dig a furrow so that the second can dig in even deeper. A study done by the U.S. Navy found that the use of tandem anchors yields a 30% improvement over the sum of their individual holding powers.

One more important note: Chafe gear is essential on any line, but it's especially important on mooring and anchor lines. Recent storms have given dramatic evidence that a boat anchored or moored is especially vulnerable to chafing through its pennants. Unlike a boat at a dock, which is usually more sheltered and secured with multiple lines, a boat on a mooring is more exposed to wind and waves and will typically be secured with only two lines. Lines on the latter will be under tremendous loads and will chafe through quickly if they aren't protected.

Trailerable Boats

A trailer is, or should be, a ticket to take your boat inland to a more sheltered location away from tidal surge. But your boat won't get far on a neglected trailer that has two flat tires and rusted wheel bearings. Inspect your trailer regularly to make sure it will be operable when it's needed.

Tip

If you take your boat home, you may want to leave it, and not your car, in the garage. A boat is lighter and more vulnerable to high winds than a car. If this isn't practical, put the boat and trailer where they'll get the best protection from wind, falling branches, and other hazards. Let some air out of the trailer tires and block the wheels.

Increase the weight of lighter outboard boats by leaving the drain plug in and using a garden hose to add water. (Rain will add a lot more water later.) This has the added advantage of giving you emergency water (not potable) if the main water supply gets knocked out by the hurricane. Place wood blocks between the trailer's frame and springs to support the added weight. On a boat with an inboard or sterndrive, remove the drain plug so the engine won't be damaged by flooding.

Secure the trailer to trees or with anchors or augers. Strip all loose gear, bimini tops, canvas covers, electronics, and other items and then lash the boat to the trailer.

Boats On Lifts

When asked, "Where wouldn't you want your boat to be in a hurricane?" just about all of the BoatUS CAT team members consistently say they wouldn't want their boat to be on a hoist or lift. Damage to boats on lifts has been high and has included boats being blown off cradles, bunk boards breaking (and spilling the boats), boats grinding against lift motors and pilings, boats being overcome by the storm surge, and boats filling with rainwater and collapsing lifts. The boats that do survive were typically subjected to only a slight surge, and the lift had been secured so that the boat and its cradle couldn't be tossed around by the wind, and the boat was covered to reduce the weight of rainwater.

Whenever possible, boats on lifts or davits should be stored ashore. If the boat must be left on its lift, remove the drain plug so the weight of accumulated rainwater won’t collapse the lift. If the tidal surge reaches the boat, it will be flooded, but leaving the plug in place is likely to result in more serious structural damage. Tie the boat securely to its lifting machinery to prevent the boat from swinging or drifting away. Some boats survived on their lifts when their owners used heavy straps to attach them to well-secured cleats on the dock. Plug the engine’s exhaust outlet and strip the boat. Make sure cockpit drains are free of debris.

Boats On High-Rise Storage Racks

In Hurricane Wilma alone, three large steel storage racks with thousands of boats collapsed. Typically, older storage racks are more vulnerable than ones that were constructed in the past few years. On newer buildings, the supports will be free of rust and the "loosening" effect of previous storms. Newer ones are also more likely to have been built to a higher standard with more and heavier structural supports to withstand higher winds. A marina owner should know how much wind a steel building was designed to withstand. If not, or if there is any doubt about the structure’s ability to stand up to an approaching storm, boats on storage racks should be placed on trailers and taken elsewhere.

Is Your Marina Stormproof?

Here are eight things to look for when it comes to selecting a hurricane-safe marina:

1. A Plan

A marina should have a comprehensive hurricane plan that outlines who does what when a storm approaches. Slipholders may have to sign a pledge to secure their boats properly, whether ashore on in the water, which can prevent your boat from being damaged by someone else's. A "hurricane club" (often with a deposit) can guarantee you'll be among those hauled out first.

2. Protection From Wind And Waves

Open water is the biggest enemy of boats in a marina during a storm. Look for tall breakwaters and small openings to the big water outside. Smaller breakwaters may be underwater during a surge. Bulkheads should be tall and sturdy and not in need of immediate repair. High banks around the marina can help keep the worst of the wind at bay.

3. Floating Docks

These should have pilings tall enough to keep the docks from floating away during a high surge (even a Category 2 will have surge of 6 to 8 feet or more). Cleats should be heavy and well-attached.

4. Fixed Docks

These should be sturdy without loose pilings or rotting wood. Taller pilings make it easier to attach longer lines to help with surge. Cleats need to be thru-bolted through substantial structure in wood docks. Loose planks can be carried away in the surge, making accessing your boat after the storm harder and more dangerous. For all docks, larger slips allow more room for movement without banging into the dock.

5. Haulout Facilities

If your marina can't haul your boat (boats are nearly always safer ashore), you'll need to move your boat to another one, which may be hard to do when a storm threatens.

6. Ashore

Higher ground for hauled boats mean less likelihood of being toppled by high water or even washed away. The best marinas have anchors in the ground that boats can be strapped to.

7. High-Rise Storage

Only those built fairly recently are designed to withstand real hurricane force winds. Most built in the last few years are, but ask your facility.

8. Marina Office

Buildings should be on high enough ground to survive the surge, otherwise management may take months to clean up, access records, and operate again.