Advertisement

There are moments in the boating life — and water over the floorboards is one of them — when problems can begin cascading, and every decision becomes crucial.

"Douglas!” I called to my husband after looking below and seeing the carpet sloshing around. “We’re taking on water!” On a boat making an offshore passage, nothing focusses the attention faster than water over the floorboards. Douglas leaped from the first real sleep he’d had in 24 hours and started checking the bilge and seacocks as I pulled up the companionway floorboard covering the packing gland.

Sure enough, as the prop shaft spun, our “dripless” gland was auditioning as a lawn sprinkler. I rushed to the helm and turned off the engine, stopped the shaft from turning, and stopped the influx. We eased the sails and Ithaka straightened up from her heeled position as Douglas started pumping the manual bilge pump under the engine where water pooled before spilling into the deeper bilges under the main saloon. Our pulses calmed as we began emptying the water and cleaning up our galley and main saloon, which had looked like a lap pool. Scary.

It had already been a notable 24 hours. We’d transited the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal with the outgoing tide the night before. Then, still in darkness and fog, we’d sailed 70 miles down the side of the choppy Delaware Bay shipping lane amid countless other boats, tankers, and tugs towing barges. Even after dawn, the fog was solid and visibility zero. For hours we’d had to navigate with radar, use horn signals, and give sécurité position updates over the VHF, listening to similar updates from the other boats and ships. We noted their positions, speed, and directions, and made sure we were giving one another plenty of passing room. At the mouth of the Delaware, off Cape May, in driving rain, we’d finally motorsailed around the shallow Prissy Wicks shoal, and out into the Atlantic. Blessedly free of land and shipping dangers, and with a long, sleepless night and day of hard sailing and motoring against tides behind us, we’d turned northeast toward home, Newport, Rhode Island, breathing a sigh of relief.

And now this …

Ithaka trotted along at a slower but steady clip under sail as we checked the packing gland and compared it to the pictures in the owner’s manual. It looked like the seal was wearing out after only three years of service. Very annoying. We had a replacement seal already secured higher on the shaft so that a change could be made without pulling the shaft. The owner’s manual had cheerful step-by-step instructions about how this could be accomplished with the boat in the water. Really? That seemed a highly dangerous proposition. When we pried the seal loose it would send a fire-hydrant blast of water into our faces. We could see no way, even if one could get the old seal off, that we or anyone else would ever be able to slip the new one into place against such powerfully gushing water. We still had cellphone reception near the coast and called the company to ask for advice.

“WHAT!?!?!” the service engineer screeched into the phone when Douglas asked him about his manufacturer instructions.

“WE said that? Wow! I mean, I guess you COULD do it. But between you and me, man, you’d better be tied at a shallow dock, plugged in, and have a couple of mother bilge pumps honking that water out.”

But he told us what we needed to know, that the seal would be safe, albeit weepy, until we could haul out in a few days’ time – unless we used the engine, which would allow water to spray in through the rotating shaft.

Get hurricane-ready with BoatU.S.

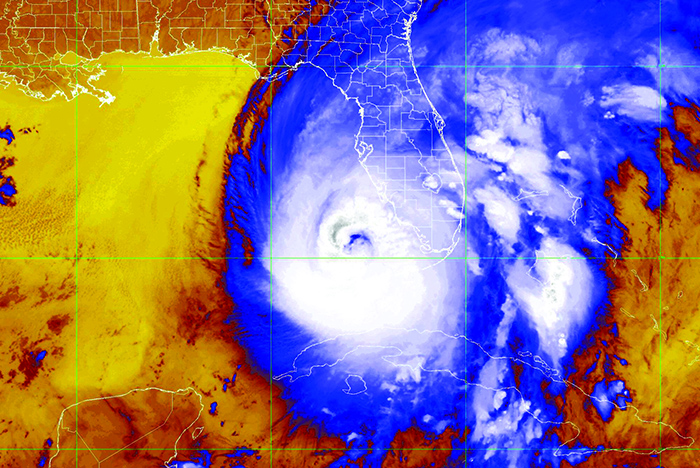

June 1 marked the official kick-off to the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season. While the number of last year’s storms were near-average, Hurricane Ian made landfall in southwest Florida as a Category 4. Colorado State University released its annual seasonal hurricane forecast in April. While the peak of hurricane season doesn’t arrive until September, now is the time to prepare if there’s any chance your boat could be in the path of a storm.

BoatU.S. makes it easy to get things in order. Visit BoatUS.com/Hurricanes for everything you need, step-by-step to ensure you have all the knowledge and supplies to give your boat the best chance of being around for next year’s boating season.

- View the BoatU.S. Active Storm Tracker to follow the latest information on any storms in the Atlantic.

- Download our free how-to guides, including the BoatU.S. Magazine Hurricane Preparations guide, the BoatU.S. Hurricane Preparation Worksheet, and the marina preparation guide.

- Watch true how-to videos from our experts on how to specifically prepare your boat, choosing the best place for your boat during a storm, and much more.

- Access our extensive library of hurricane articles to help you make the best decisions and preparations possible.

- Download the BoatU.S. App and turn on notifications to receive real-time updates on storms that may be headed your direction.

— STACEY NEDROW-WIGMORE

Oh, but there’s a twist!

We had several choices. One, we could relive the nerve-wracking, exhausting rigmarole of the night before, in reverse. But to do that, we’d have to motorsail all day against a wicked tide, and back up Delaware Bay in still-thick fog, dodging tankers, then motor back through the 14-mile C&D Canal on the right tide, and look for a boatyard in the Chesapeake, taking turns manning the bilge pump every half-hour – such an unappealing option. Two, we could sail north up the Atlantic coast to New Jersey and put in someplace where we could arrange to haul out – an option we decided had too many unknowns, considering the weather was swiftly deteriorating. Three, we could carry on, sailing 220 miles home to Rhode Island without using the engine. After all, this was a sailboat, right?

There was another option, of course – to call the local TowBoatU.S. operators and ask their advice in recommending a place to haul out. They were always helpful. This would’ve been the smart move under normal circumstances – and these guys always had enlightening advice – but there was another significant factor at play. Within 48 hours, a hurricane that had suddenly shifted direction and predicted landfall was now forecast to start hammering the Chesapeake with 120-mile-per-hour winds and flooding rains, which meant local marinas and boatyards were all filled with regular customers. We and many other transient boaters had, literally, nowhere safe to haul or tie up. We all wanted to get our boats out of harm’s way, fast – which meant as far from where we were as possible by the time the hurricane hit. For Ithaka to do that, we’d need to average at least 5 knots to Newport.

This is the stuff of almost every serious boating decision – nothing clear-cut, every solution carrying its own price. Douglas and I agreed that we just couldn’t risk wasting this crucial escape day trying to find a place to secure our boat, and then either have that place get hit full force by this hurricane with the resulting storm surge or, even worse, that we may very well fail to secure a place at any marina and then have to find a decent hurricane hole in which to anchor – with a packing gland we couldn’t trust, spewing seawater every time we used the engine. Not good.

The newest forecast had the wind in the hurricane strengthening and the clock ticking. The freshening wind helped us make the call. It was strong and getting stronger, from the southwest, and forecast to stay that way for at least 24 more hours, which would put it at our backs if we sailed northeast. Ithaka would fly at 9-plus knots in those excellent sailing conditions. We talked it over, decided to go, then trimmed the sails and headed 220 miles toward home. It was quite a sleigh ride, as they say in sailing, as we flew north.

12 Lessons That Could Save Your Life

1. When a hurricane is forming, assume it will change course several times as it approaches landfall. DO NOT WAIT. Take evasive action immediately to secure your boat, and then get yourself to safety.

2. It’s critical to be able to follow the NOAA marine weather forecasts whenever you’re aboard your boat. You can’t rely on smartphone apps. Make sure you have a DSC-enabled built-in VHF, or other receiver such as single-sideband radio on your boat and a backup handheld waterproof VHF.

3. One bilge pump is not sufficient, no matter the size of your boat. You need at least two electric bilge pumps (one large-bore) and one manual bilge pump. Installing a bilge alarm will alert you to water rising in the bilge before you can see it over the floorboards.

4. When there’s a leak below the waterline, time is of the essence. You must be able to find it by swiftly checking the shaft and every single seacock and thru-hull fitting, in the dark, by feel (also the keel bolts, if applicable). Can you do this? If not, it’s time to practice. To ensure that you know exactly where every seacock and other potential breaches are, so you can find and close them if water already has covered them, practice this in the dark to gain confidence. You should have a soft-wood bung (plug) of the correct diameter tied by a string to every single thru-hull (buy them at West Marine). If water is flowing in through a failed thru-hull fitting, or especially through a thru-hull impeller, use this bung to plug the opening if it will to stop or stem the flow of water. Seacocks must be lubricated every year to ensure they open and close easily. (Some lube products work poorly underwater, so check to see what the seacock manufacturer recommends.)

5. It’s more likely that a ruptured hose will be the cause of your leak. Maintain your hoses and regularly check your hose clamps for rust. Use TWO marine-grade stainless steel hose clamps at each end of a hose, not one. If one corrodes, the other is a backup. A good choice is Awab clamps, which have rounded edges, no holes, and are fully stainless. Rescue tape can temporarily repair most hose leaks and can be applied while wet or while water is coming in.

6. Keep owner’s manuals for all major systems aboard your boat so you can refer to them immediately when things go wrong. Use common sense; if something feels dangerous, trust your gut. If you can wait to fix something until you’re safely at a dock or hauled out, that’s often the best approach.

7. We always have an EPIRB, life raft, and ditch kit at the ready, and we always wear inflatable life jackets/harnesses tethered to the boat while on watch from dusk to dawn. Harnesses have a strobe light, whistle, and solid light. Our rule is anyone coming into the cockpit at night MUST wear their harness and clip in BEFORE stepping through the companionway.

8. It’s not mandatory to have radar on your boat, but if you have it, always use it when operating in areas of restricted visibility.

9. Use horn signals according to the inland and international Navigation Rules.

10. When it’s dark or the fog rolls in, eliminating your visibility in a busy shipping lane, you can use VHF channel 16, which is used ONLY for hailing, to give a safety message, called sécurité (se-CURE-ih-tay), to other boats within close proximity. Speak clearly into the microphone: “Sécurité, sécurité, sécurité. This is the XX-foot [power, sailing, fishing] vessel [boat name] traveling [direction] at XXX degrees, in [zero, limited] visibility at X knots just off [location]. My position is XXXXX latitude, XXXXX longitude. Standing by for any concerned vessels on channel 16 and 13.” Then switch to channel 13 and repeat the same message. Channel 13 is the commercial bridge-to-bridge channel. Skippers from nearby vessels who follow you to the new channel can answer you. Then you both can determine your courses and headings, and discuss how you’ll pass each other safely. You’ll need a chart of the area and GPS to accomplish this.

11. When you have a mechanical problem, as soon as possible issue a sécurité as described above, and state your problem so that other boaters and TowBoatU.S. will become aware of it and learn your location. If the problem worsens, broadcast a “pan pan” message, which is reserved for those with an urgent problem that is not life-threatening at the moment. If you lose the ability to communicate, however, you’ve identified your position and problem — a crucial first step in case help is needed. “Mayday” is reserved for situations where human life is in danger, and rescue is requested.

12. When making a voyage, or taking your boat out of sight of land, give your float plan (your planned route and ETA) to someone responsible who’ll know right away if you’re overdue. Also, make sure your registration information for your EPIRB or GPIRB is up to date, and that you have up-to-date emergency-hailing equipment such as current flares. — B.B.

Blessed landfall

Forty hours later, Ithaka made safe landfall in Newport Harbor, soaring in like a tiger under sail. The following day, a hurricane clocking 105 mph hit the Mid-Atlantic states with deadly force, bringing with it a devastating storm surge that flooded cities, and carved up Hatteras Island in North Carolina with new inlets.

Isabel had been identified as a Category 5 hurricane only three days before it hit land; the hurricane warning hadn’t been issued until only two days before its landfall in North Carolina. The aftermath revealed 16 hurricane-related deaths, $3.6 billion in damage, hundreds of thousands of evacuations, 6 million households without power, the closing of 19 major airports, and the U.S. Navy evacuating aircraft carriers, submarines, and dozens of aircraft from Norfolk, Virginia.

The GEICO | BoatU.S. Catastrophe Team, which sets up its impressive mobile operations immediately after hurricanes in the hardest-hit regions, to help its insurance clients, was there the minute they could get in and set up safely, and reported 24,000 boats damaged.

Douglas and I were lucky. The strengthening winds had carried us home and away from the greater danger. We were able to sail Ithaka through the crowded Newport Harbor and to our mooring without the engine. By the time the highest winds hit New England on September 18, we’d stripped the boat of all her canvas and every bit of windage, reinforced her mooring lines, padded them at any chafe points, and got ourselves home, where we watched the heartbreaking news coverage on television. We’d come very close to having a far different ending to our story.