Advertisement

Our oceans and waterways cannot absorb the amount of plastic going into them. Here's an update on the state of the gyres and a look at some of the ways we're trying to clean them up.

Photo: Shutterstock.com/Rich Carey

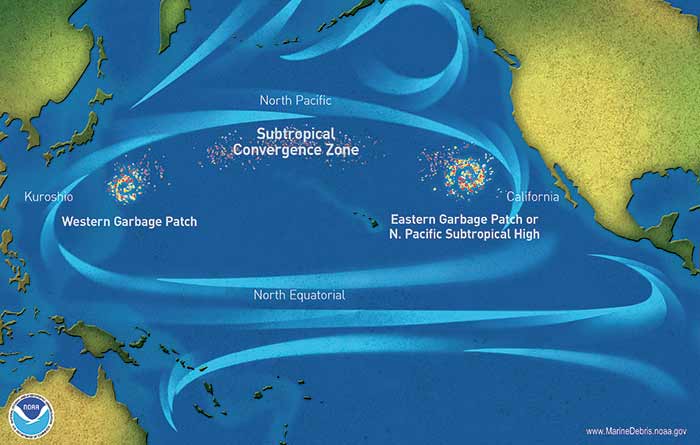

Take a massive area of ocean. Add swirling currents from wind and the earth's rotation. Gradually mix in plastics of all types and sizes. Bake well under ultraviolet rays while stirring continuously for decades. This is the not-so-tasty concoction that makes up our world's gyres — the natural phenomenon of rotating currents that appear at 30 degrees north and south latitudes of the North and South Pacific, North and South Atlantic, and Indian oceans.

An estimated 8 million metric tons of plastic floating debris enters the oceans each year. Some washes back on our shores or sinks in coastal waters. The rest accumulates in the centers of these undefined gyres. Called "garbage patches," they're not so much islands of trash as many people imagine, but instead they're "like pepper flakes swirling in soup," according to Sarah Lowe of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program.

Sizing Up The Problem

Though plastics are spread throughout all the oceans, the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch" is probably the best known and most studied due to its location between California and Hawaii. It was first named and publicized in 1997 by a boater, Captain Charles Moore, on his return voyage from the Transpac sailboat race. He encountered piece after piece of plastic waste floating by. Two years later he founded Algalita, a marine research and education organization focusing on plastic pollution and its impacts on marine life and ecosystems.

The actual size of these gyres cannot be precisely measured because the borders and content constantly change with ocean currents and winds. But we do know that the North Pacific subtropical convergence zone (created by the interaction of the California, North Equatorial, Kuroshiro, and North Pacific currents) for instance, is roughly estimated to be around 7.7 million square miles — an area approximately the size of Canada and the U.S. together. Algalita is preparing to publish a 15-year retrospective study that reveals a significant increase in the amount of garbage in the gyres. Education director Anika Ballent reports that 15 years ago, Algalita took samples in 11 areas of the North Pacific gyre and counted the number of plastic pieces per square kilometer. Ballent reports that, at that time, they found six times more plastic than plankton. By 2014, similar sampling methods showed the plastic-to-plankton ratio had increased tenfold — 63 times more plastic than plankton.

Advertisement

The Root Of The Problem

Not surprisingly, 100 percent of the plastic detritus churning in our world's oceans originates with human activity. The majority of it comes from land-based consumer waste, such as discarded bottles, preproduction resin pellets used in the manufacture of plastic goods, microbeads from cosmetic products and industrial finishing abrasives, and even microfibers from synthetic fabrics. High winds and heavy rains during natural disasters — hurricanes, mudslides, tsunamis — introduce large amounts of debris into surrounding waters. The rest comes from fishing nets, buoys, traps, and trash dumped overboard by commercial and recreational boaters.

"Every country contributes to the problem," says Lowe. "But some countries have better waste-management practices than others." She emphasizes that even non-coastal areas are problematic. "Trash goes into streams and rivers, and eventually ends up in the ocean." Ballent puts it more succinctly: "Coastal environments are downhill from everywhere."

Without anywhere else to go, larger plastics break down into smaller and smaller pieces over time. This microplastic "is smaller than 5 mm, the size of a pencil eraser," explains Lowe. And a growing concern is the plastic pieces that are invisible to the eye: Nanoplastics are smaller than 100 nanometers (0.0000010 mm). Micro- and nanoplastics are churned deeper into the water column by wind and waves, eventually ending up in the food chain.

They're Making A Difference

Here are some of the leading organizations working to solve the problem of plastics in our water.

5 Gyres Institute

Nonprofit, founded in 2009, focuses on research and education at the corporate and government level. To raise awareness, co-founders Marcus Eriksen and Anna Cummins built a raft of plastic bottles and floated the Mississippi River from Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico; used 15,000 plastic bottles to float a Cessna airplane from Los Angeles to Hawaii; and have sailed into all five subtropical gyres to document the levels of plastic pollution.

Algalita

For 20 years a leading research organization focused on plastic pollution's impact on marine life and ecosystems; and stopping the flow of waste into the marine environment through education and technological developments.

Keep America Beautiful

A national organization dedicated to ending littering, improving recycling, and beautifying communities, with more than 620 local affiliate organizations nationwide. Each spring, Keep America Beautiful organizes the Great American Cleanup to clean up litter in communities, which mobilizes 5 million volunteers and collects more than 320 million pounds of debris.

Marine Affairs and Research Education

Nonprofit, serving coastal and marine resource managers with global programs to network them with peers, despite their location or financial means. Launched MarineDebris.Info to provide a free, continuous forum for global discussion and news among marine-debris scientists, industry, resource managers, policymakers, conservation organizations, and stakeholders worldwide.

NOAA Marine Debris

Since 2006, this U.S. Federal program offers competitive funding for marine-debris cleanup projects; spearheads national research efforts; and works to change public behavior through education. A free mobile app, the Marine Debris Tracker, was developed to allow users to help make a difference by reporting when they find trash on coastlines and inland waterways.

Ocean Conservancy

This 45-year-old nonprofit helps formulate ocean policy at federal and state levels based on peer-reviewed science. Organizes annual nationwide shore and waterway cleanups (this year's cleanup is September 17, 2017), and counts 900,000 volunteers and members, who've removed 145,000 pounds of trash from beaches over 25 years.

Plastic Pollution Coalition

Founded in 2009 to build a global alliance of member organizations, businesses, and leaders working together to develop alternatives to single-use (disposable) plastic containers, the coalition's three-pronged approach involves education, advocacy, and science-based solutions.

Rozalia Project

Co-founded in 2010 by boaters Rachael Miller and James Lyne. The recipient of two BoatUS Foundation grants, this nonprofit focuses on cleaning the ocean of non-biodegradable debris that can be ingested by sea life then, subsequently, by humans. The organization has recently taken on the issue of microplastics from synthetic clothing with the launch of its CoraBall microfiber catcher, which was set to launch in July after a successful Kickstarter campaign.

The Ocean Project

In partnership with aquariums, zoos, museums, and other youth and visitor-serving organizations around the world,, provides opinion and market research, strategic insights, and support for innovative and effective public-engagement programs. Since 2002 they've served as the global coordinator of World Oceans Day, collaborating with organizations in more than 100 countries.

— Rich Armstrong

Why Does This Matter?

Aside from vessel damage caused by debris, including tangled props and clogged intakes, plastic in our water hurts the boating environment, the economy, and resources, such as the seafood we consume.

"Plastic is not a natural material, so nature can't get rid of it or digest it," says Ballent. Larger plastics, like discarded fishing nets, monofilament, and six-pack rings, can entangle and kill marine life. But the smaller pieces can be as much or even more harmful.

It's unknown how long plastics take to decompose, because synthetic plastics have only been around for about a century and in widespread use since the 1940s. Estimates range anywhere from 450 to 1,000 years, depending on the type of chemicals used and the method of production. This figure, however, is more accurate for plastics buried in landfills that are not exposed to ultraviolet rays from the sun. Unlike organic waste, plastics don't biodegrade; most bacteria won't digest them. They do photodegrade, however, which means the effect of the sun breaks them into smaller and smaller pieces. This makes plastics particularly problematic in the oceans.

Micro- and nanoplastics have been found in all marine life, from plankton to whales. Research has shown that approximately 25 percent of the fish caught around the world contain plastics. When fish ingest plastic instead of food, many die from malnutrition or starvation or are eaten by predator fish, and the plastic moves up the food chain.

Chemicals both from the plastics themselves as well as from organic pollutants that attach themselves to the surface of the plastics, are absorbed into the tissues of the fish and are eventually ingested by humans. These chemicals have been linked to cancer, malformation, and impaired reproductive ability in other animals.

Long-Term Solutions

"We need to change the system that allows it to happen in the first place," says Ballent. "Plastics aren't bad.

It's our use of them that isn't well thought out."

Joost Dubois, head of communication for a nonprofit technology organization called The Ocean Cleanup, agrees: "In general, it's a good material, but we've made mistakes in how we use it. Having it end up in the oceans is a big problem."

Ballent suggests that a good start is for people to become conscious consumers. "Change your relationship with plastics," The cleanup debate she recommends. "Use your dollars to vote for responsibly made and thought-out products. Look at packaging. Get rid of single-use plastics. Buy products that are more sustainable." (See "What Can You Do?" below for suggestions.)

The Cleanup Debate

The one solution that remains controversial, surprisingly, is cleanup. "You can't drain the bathtub unless you turn off the tap," says Ballent. Algalita doesn't participate in cleanup efforts, she says, instead preferring to focus on prevention. NOAA has a network of regional partners, each with strategic action plans that coordinate groups in that area. Lowe says, "NOAA funds many small-scale removal projects in the U.S. to keep trash from getting into the environment in the first place. But given the scope and scale of the problem, prevention is key."

A computer rendering of what The Ocean Cleanup's floating booms will look like. To avoid collisions, they will be equipped with AIS as well as reflectors that will show up on radar. (Photo: Erwin Zwart/The Ocean Cleanup)

On the far side of the cleanup scale are some innovative new ideas, such as The Ocean Cleanup, that harnesses the rotating currents of the gyres themselves to passively collect larger trash. Here's how it works: A floating "boom," or barrier, with an impenetrable screen extends underwater 5 to 10 feet. "The shape allows for a concentration of plastic into the center for collection," says Dubois. "The center has a retention system to keep the plastics in place despite wind and weather. Every two weeks a vessel will pick up the refuse and bring it back to shore, where it will be recycled."

Tip

The Ocean Cleanup is already testing working models and is on track to have full-scale deployment in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 2020. Dubois says, "Calculations show that with the use of our technology, half of the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch could be cleaned up in 10 years using 100 kilometers [62 miles] of barrier." The company is working with a team of external experts to minimize the risk to marine life, such as animals becoming entangled in the screen.

The Ocean Cleanup was founded in 2013 by then 17-year-old Boyan Slat of the Netherlands. Dubois says the majority of the initial funding was crowdsourced, with nearly 40,000 people around the world contributing $22 million toward the project in 100 days. Other funding comes from individual and foundation donations, in-kind support, and sponsorships.

What about government funding? "A large barrier to cleanup," explains Dubois, "is that according to international maritime law, no one owns the problem, legally speaking. Therefore, relatively little money has come, or is expected to come, from governments." The Ocean Cleanup received a half-million Euro subsidy from the government of the Netherlands for its prototype in the North Sea. Aside from these approaches, Lowe emphasizes that regulations are just one possible solution and that, when given the choice, "most industries prefer to work toward solutions voluntarily." To that end, NOAA includes many industry representatives, including the BoatUS Foundation, in its regional action plans. "It's a slow process," says Ballent, "but the more people who get involved, the quicker it will happen." The gyres of the world once seemed like a problem far, far away — one we could not see and one that did not really affect us. But that ocean plastic is building up to be a bitter soup that can't be digested, and it won't go away by itself.

What Can You Do?

- Practice the three "R"s: reduce, reuse, recycle.

- Dispose of trash properly, while on land and water. Secure discarded items on the boat so they don't go overboard.

- Get involved with local cleanups on beaches and waterways. Find events in your area.

- Support "clean marinas" by docking in them. Learn more and find a clean marina.

- Carry a reusable drinking container.

- Avoid using single-use disposable plastic items, like utensils, straws, and takeout containers. Use durable fabric shopping bags.

- Recycle discarded monofilament in bins located at many marinas. Learn more about this program and to find out how to build your own recycling bin.