Advertisement

Spare your engine compartment from costly repairs by following these important regular maintenance tips.

Your diesel engine will give you many years of reliable service if you give it the TLC it requires. (Photo: Volvo Penta/Magnus Ecklöf)

The deed is done, and it is murder most foul. Your loyal diesel engine has met an untimely end, cut down in the prime of its expected service life. Who's responsible? Colonel Mustard in the library with a yeti paw? Miss Scarlet in the foyer with a loofah? No. It was you who murdered your diesel due to lack of maintenance! Let's consult with the world's greatest detectives and sleuth through the clues at the scene of the crime to uncover the surprisingly simple ways you ushered your engine to an expensive and early demise.

Clue No. 1: It's elementary, my dear Watson. The owner failed to change the oil. It doesn't require a visit to 221B Baker Street to discover regular oil changes are the single most important thing you can do to maintain the life of your engine. Most engine manufacturers recommend oil changes every 100 hours, or annually at a minimum. Some engine manuals may allow longer intervals, but more frequent oil changes (rather than stretching out the periods between them) are a better strategy to extend the life of the engine.

An outdated oil filter.

This is particularly true for diesel engines, which tend to be harder on oil lubrication properties than gasoline engines (one reason many experts suggest the oil for diesel engines be changed every 50 hours of use rather than the 100 hours commonly quoted). While it should go without Sherlock saying it, always install a new oil filter when changing the engine oil.

Clue No. 2: "All we know are the facts, ma'am." states Detective Joe Friday. "It's obvious that the owner failed to test the engine warning alarms." "Most all engines have temperature and oil pressure alarm systems consisting of audible and visual alarms, and these can fail over time," notes Capt. Mike Monteith of Horizon Marine in Norfolk, Virginia.

"In many of the catastrophic engine failures we see due to overheating or loss of oil pressure, the alarm system was inoperative, a problem that went unnoticed by the operator. While not a direct cause of engine failure, failure (or lack) of the audible alarm is a major contributor." Most engine manufacturers use the same buzzer for multiple monitoring systems — oil pressure, engine temperature, and sometimes alternator output. The problem is that the buzzer can sound if one (or even two) of the three monitoring circuits has failed.

When you turn on your engine ignition, the buzzer you hear is confirming operation of the low oil pressure alarm. Placing the engine ignition in the on position without actually starting the engine simulates a low or no oil pressure situation — the ignition is on, but there is no oil pressure as the engine is not running. If you don't hear this alarm when starting your engine, chances are there will be no alarm if loss of oil pressure should occur.

Advertisement

While this simple test verifies that the low oil pressure monitoring circuit is working, it doesn't confirm that other engine alarms (engine overheat or alternator output) are functional. As mentioned previously, one or both of these could be faulty, even if the buzzer sounds at engine start up.

"In almost half the engine helm systems I inspect, the audible alarm system has long since stopped working properly, typically due to a broken sensor wire or corroded connections" says Monteith. "In many cases where the engine overheats, the cause of many engine failures we see, the alarm is not operational. By the time the operator notices the problem, either by glancing at the temperature gauge or smelling the overheating engine, the damage is already done."

The operation of engine warning alarms should be verified at least every two or three years, something that can be easily done by your mechanic.

Clue No. 3: Oh sir, just one more thing, you didn't change your fuel filters. Columbo knows fuel filters always seem to clog at the worst possible moment, such as running a narrow inlet or when navigating a busy harbor. Causing your engine to shut down during a crucial evolution is bad enough, but it gets worse: Clogged fuel filters can also damage injectors and injection pumps.

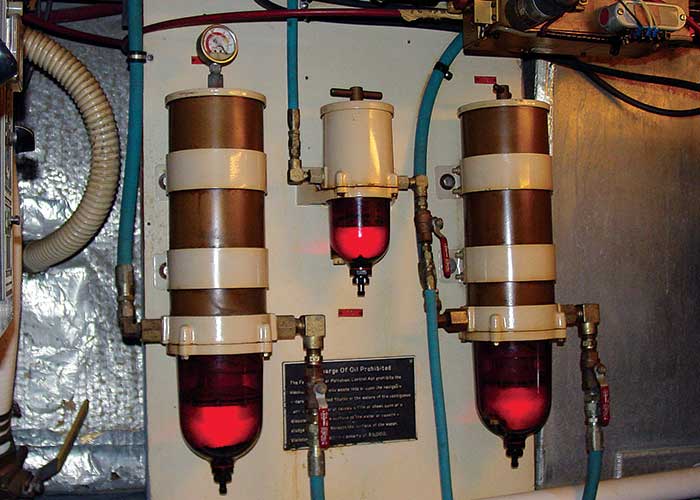

Duel primary fuel filters.

Diesel fuel injection systems create a lot of heat, and they rely on unobstructed fuel flow to keep things cool. In extreme cases, excess pressure from a clogged filter can cause filter damage, allowing a failed filter to dump contaminants or even pieces of the filter itself directly into the injection system. Fuel filters should be changed regularly with replacement dates logged (along with engine hours) as part of your vessel's preventive maintenance program.

Clues that indicate your filters need changing? In addition to the classic signs accompanying a fully clogged filter (engine surging followed by complete shutdown), many engine problems that initially appear to be mechanical in nature can often be traced to a clogged filter. These include missing, surging, reduced power, and excessive black smoke.

A good way to monitor fuel filter condition is to install a vacuum gauge. Little or no vacuum means the filter is clean; high readings on the vacuum gauge indicate the engine is "sucking" harder to get fuel through the filter, a sign that it's clogged and needs replacing.

Vacuum gauges can be inserted into the line between the primary fuel filters and lift pump or in many cases screwed into the top of the primary filter housing cap, replacing the "T" handle. Be sure to keep the handle mounted near the filter for emergency use should the vacuum gauge fail. While gauge markings vary (some simply have green, yellow, and red zones), in general, if the gauge shows 5 or more pounds of vacuum while the engine is running, the filter element needs replacing.

Clue No. 4: Observe, No. 1 son — the air filter has not been replaced! You don't have to be as smart as Charlie Chan to see a pattern here regarding the benefits of routine maintenance. Even simple ones, such as maintaining your air filter, can make a big difference when it comes to increasing your engine's service life.

Black exhaust smoke, loss of power, increased fuel consumption, and overheating are all possible clues that your air filter needs to be replaced. A clogged air filter can also cause your engine's turbo (if so equipped) to spin faster in attempts to provide the engine with adequate air flow. Severe damage to valves, pistons, and the turbo itself can occur if contaminants from a clogged air filter are ingested by your engine.

Bad air filter.

Clue No. 5: Read the smoke signals — six, two, and even, over and out! It doesn't take a two-way Wrist Radio (or bulldog jaw) for detective Dick Tracy to communicate the cause of your engine's demise. Exhaust smoke is your diesel's way of telling you what's going on, and correctly reading the signs can head off potentially expensive repairs. A well-maintained engine may smoke when initially cranked or while idling but typically not while under load.

White smoke during startup of a cold engine is normal, but it should clear up once the engine warms up. If it continues, it's normally an indication of unburned fuel, but it can also be a number of other issues from water or air in the fuel to a faulty injector, injection pump, blown head gasket or even a cracked cylinder head or liner.

White smoke coming from the engine compartment.

White smoke can also be a sign of engine overheating, however, the "smoke" in this case would actually be steam produced as raw cooling water passes through the exhaust system. Overheating due to a clogged exhaust elbow would be a good example.

Black smoke upon start up is also common, however, its presence after the engine is under load indicates incomplete combustion. Possible causes range from air intake or exhaust restrictions, compression problems, and faulty or worn injectors to engine overloading due to an oversized or overpitched propeller.

Blue smoke means the engine is burning oil, which is also not uncommon at startup. Continued smoking, however, may indicate trouble with valve guides and stems, worn piston rings, or failing turbo-supercharger oil seals.

Clue No. 6: You poisoned your engine, Monsieur! While not as exciting as Murder on the Orient Express, follow Hercule Poirot's advice to use your "little gray cells," and you'll soon surmise that many marine diesel problems originate in the fuel tank.

The key to keeping a diesel engine happy is clean fuel. The reason for all of this clean fuel hubbub has to do with your engine's fuel injectors. These precision-tuned components deliver a precise, ultrafine mist into the combustion chamber. They don't like contaminants one bit, and even microscopic specks of dirt or water can wreak havoc on the combustion process (as well as your injectors and Junior's college fund).

Advertisement

Not surprisingly, water intrusion is a major source of diesel fuel woes for boats. That deck fuel fill cap with the missing O-ring is a perfect path for water entry into the fuel tank during every washdown or rainstorm.

Diesels use pressure to generate combustion, and when water enters the engine it turns to steam, which can literally blow your injectors to pieces. Water also mixes with the sulfur in your fuel to create sulfuric acid (sort of like the blood of those "Alien" movie critters), which can cause internal engine parts to corrode.

Limited or seasonal use is also an issue when it comes to boat fuel. Despite the plethora of magic potions and elixirs sold to "kill bugs" or stabilize your fuel, diesel stored onboard for long periods can still degrade or become contaminated due to microbial or bacterial growth. As water enters your fuel tank, it eventually separates and settles to the bottom — a common problem with fuel stored long-term. That's when things get buggy.

Microbes thrive in this water and their only goal in life is to eat and multiply. Sure, you can add biocides after the fact and kill the little troublemakers, but as any good hit man knows, killing is the easy part — the problem is disposing of the bodies. In the case of dead microbes, they'll lie in wait at the bottom of your tank until that first rough passage, then rise up zombie-like to clog filters and, in general, wreak vengeance on your fuel system and worse still, your engine.

Filter funnel.

While you should always use a filter funnel when taking on fuel, the best strategy is to take on fresh, clean, water-free fuel to begin with. Choose marinas that have a high rate of fuel sales (and thus fuel turnover). One of the best marinas I've seen in this regard was located beside a major highway and also served as a truck stop.

If you have any doubts about the cleanliness of the fuel down at the Rake ‘n' Scrape Fritter Shack & Marina, pump a small sample into a clean glass jar before fueling and let it sit a few minutes after which any water and dirt present will settle to the bottom. If you see either, buy your fuel elsewhere.

Clue No. 7: "The avoidance of idiocy should be the primary and constant concern of every intelligent person," lectures Nero Wolfe. That being an undeniable fact, why would a boat owner fail to replace engine manifolds and exhaust risers at the recommended intervals? Exhaust manifolds and risers are metal castings that carry hot exhaust gases away from the engine. Manifolds are located along the side of each cylinder bank, while the riser or exhaust elbow (which often resembles an inverted U) is mounted atop the manifold and is where the exhaust hose is attached.

They are double-walled (essentially a pipe within a pipe) with exhaust gases contained within the inner pipe being surrounded by cooling water contained in the external pipe (aka, water jacket). At the discharge end of the riser, water from the water jacket is combined with the hot exhaust gases, after which the mixture is then discharged into the exhaust hose and overboard.

It's not uncommon for exhaust manifolds to fail after five to seven years due to corrosion. When that occurs, water can then seep into the cylinders while the engine is not running and cause myriad problems from seized pistons (due to corrosion) to a condition called hydrolock. The latter occurs because water is not compressible, meaning the engine can suffer catastrophic damage if started with water in the cylinders.

Corroded manifold and riser.

One clue that trouble is brewing within your exhaust riser is an increase in temperature, a typical sign of reduced raw water flow. A simple way to detect this is to periodically feel or measure the temperature of the exhaust elbow during engine operation to verify it is maintaining a normal, even temperature. You can also compare the temperature of the water exiting the exhaust elbow with the ambient raw water temperature. While this temperature difference will vary between engine models, it is typically around 40 F to 60 F. In other words, if the incoming raw-water temperature is 75 F, the water exiting the exhaust elbows should be in the range of 115 F to 135 F. This increase will make the surface of the elbow warm to the touch, but not excessively hot. In any case, the exhaust water temperature should never exceed 200 F. (To avoid the possibility of a burn, it's best to use an infrared heat sensing gun. These make excellent diagnostic devices for many other issues, too.)

Rather than consider manifolds and risers permanent parts of your engine, they should more correctly be viewed as engine consumables — no different than belts or oil filters. Due to the serious potential for damage, many engine manufacturers recommend that manifolds and risers be replaced every five years. The cost of stretching this period or ignoring the recommendation altogether is obvious when considering the following statement from Capt. Monteith:

"Most all of our engine sales over the last 10 years have been a result of failing to replace the exhaust manifolds and risers within the manufacturer's recommended time frame."

Read that one again — I'll wait here.

Buying a boat and not sure if or when the manifold and riser were replaced? The seller says it was "a couple of years ago" but can't find the paperwork for some reason. Take another bit of advice from Nero Wolf and be a card-carrying pessimist in such cases.

"That is, of course, the advantage of being a pessimist; a pessimist gets nothing but pleasant surprises, an optimist nothing but unpleasant."