Advertisement

Average swell heights on the West Coast are significantly higher than on the East Coast, Gulf Coast, or in the Great Lakes, and can be deadly.

Coast Guard Station Golden lifeboat crews conduct surf training near Ocean Beach, California. The large swells they encounter there ensure the crews are prepared to respond to any maritime emergency during rough weather conditions. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard/PO3 Loumania Stewart)

The 6-foot comber slammed against the port bow, knocking my 34-foot trimaran sideways until it fetched up on the anchor chain with a jerk that nearly took me off my feet. A scant quarter mile behind me, enormous waves crashed against the rocks of Pebble Beach at the head of Stillwater Cove on California's northern Sonoma coast, shooting spray 40 feet into the air. I needed to leave — now — while I still could.

But I was alone, and there was no way to manually crank up the 200 feet of chain that held the boat against the assault of the relentlessly growing waves. With no other choice, I released the windlass clutch. The remaining chain roared out until it fetched up against the rope tail that secured the bitter end. I tied an orange fender to the chain, then watched the incoming wave train, waiting for what I hoped would be the right moment. I saw my chance and touched my knife to the bar-taut line. It exploded in two, and I raced back to the helm.

Tip

Slamming the throttle lever all the way forward and pointing the bow toward the next comber, I prayed the prop wouldn't foul on one of the thick patches of kelp around me, nearly invisible in the foam and spray. Time slowed to a crawl. The growl of the breakers became strangely muffled. Hanging on, I held my breath as the bow rose skyward and the steering wheel rotated down into my gut.

This was the critical moment. If I made it over the top and down the backside of this wave, I'd be out of the trap. If the boat broached or the prop fouled, I'd toss out the anchor I'd laid out on deck and pray it held. If not, I'd be hurled sideways into the maelstrom and the rocks behind me. Neither the boat nor I would survive the pounding. I'd anchored in the cove to escape swells coming out of the north. But as seas grew, it became apparent that the swells were wrapping around the south-pointing breakwater and entering what I'd thought initially would have a been a safe anchorage.

So where do you find safety in circumstances like these? It may seem counter-intuitive, but in the absence of strong winds, shelter from large swells lies in deeper water or offshore. Once I extricated the boat from the dangerous breaking waves in the shallow cove, I simply reanchored in 60 feet of water, ironically, in a more exposed part of Carmel Bay. There was little wind, so the openness of the anchorage wasn't important. What was important was that the depth was nearly three times the height of the swell. I'd already prepared the rode and anchor, so all I had to do was drop it over the side when I got to a safe place.

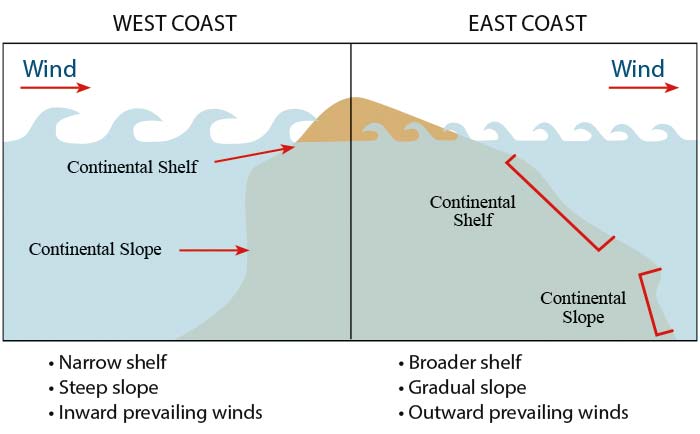

Here's why waves on the Pacific Coast are much larger than those on the Atlantic Coast of the United States.

At least I got one thing right. Thirty minutes after I almost lost my boat — or worse — I was riding gently up and down with the big swells rolling into the bay — safely anchored less than a half-mile from the scene of my recent narrow escape. In the three days I had to wait for conditions to allow me to return to recover my abandoned anchoring gear, I had plenty of time to contemplate the lessons learned from this terrifying experience.

Comparison Of Significant Wave Heights* On East And West Coasts

| Buoy Location | Percentage of time waves <3 feet | Percentage of time waves >12 feet |

|---|---|---|

| ~150 miles E of Cape Hatteras | 7% | 10% |

| ~600 miles SW of Portland | 0% | 23% |

| *Average of biggest one-third of all waves recorded during time interval | ||

Lessons Learned

If the weather turns nasty, a shallow cove can be the worst place to be. Not only will the waves break first in the shallow water near shore, but you have almost no margin of safety if your anchor drags or you need to make a quick exit like I did. Now, unless I'm absolutely sure the weather will remain settled, I drop the hook in the deepest water that is still sheltered from the prevailing wind and waves.

I also underestimated the ability of big swells to wrap around land. I knew that waves refract, or bend, around islands and points of land, but never thought that even large swells could do a 180-degree turn. I learned that when swells are large enough, the effect is almost tidal, and shallow water is hazardous regardless of the relative direction of the offshore swell.

Finally, I should have seen the error in my choice of anchorage sooner and left before it became a life-and-death situation. Much like deciding when to reef, the time to leave a potentially dangerous anchorage is the first time you think about it. Period.

Tip

I did have the sense to monitor the weather daily and seek shelter based on NOAA warnings. I picked the wrong spot. With adequate spare anchors and rode onboard, I wasn't reluctant to abandon a set of gear in order to make a quick exit. Equally important, because I'd rigged a length of rope to the bitter end of the anchor chain, I could cut it free in an instant. Before doing so, I'd readied my second anchor that I knew would set quickly even if it encountered some kelp. With the rode carefully flaked on deck so that it would pay out with no chance of fouling, all I'd need to do in case of emergency would be to toss the anchor over the bow.

I had enough line, so I could safely reanchor in deep water. In fact, I needed more than 300 feet to achieve 5-to-1 scope in an average of 60 feet of water. Finally, when things calmed down, I was able to recover my costly anchoring gear because I'd attached a large round, orange fender to the end of the chain before cutting it loose.

A few days later, I celebrated my narrow escape with a steak dinner at one of Santa Cruz's finest oceanfront eateries. Savoring a glass of fine California cabernet while surveying the damage to the harbor through the window, I realized just how lucky I was that my lesson hadn't cost me much more.

Critical Takeaways

- Very large swells will refract around points of land, changing speed, wavelength, and direction. Anchoring in water depths two-and-a half to three times the combined swell and wave height (and carrying enough rode to do so) is good insurance in case swell finds its way around a corner to you. Call the local harbormaster, if there is one, and ask where you'll be safest given the forecast.

- Wind generates waves, but waves often outlive the wind that spawned them to become swells. Of the biggest wave sites in the world, California boasts the majority, with Hawaii a close second.

- To get a feel for the difference in swell between the West and East coasts, check NOAA's National Data Buoy Center. Click on one buoy on each coast and read the significant wave height (the average of the top one-third of all waves over the interval). For instance, we averaged all the significant wave heights taken at one-hour intervals for one year from Station 41623 off Mendocino, California, and Station 44009 off Cape May, New Jersey. Waves average 3.7 feet off Cape May, less than half the 8.4-foot average off Mendocino. The table above summarizes data farther offshore, from Buoy 46006 located 600 nautical miles southwest of Portland, Oregon, and Buoy 44004 located 150 nautical miles east of Cape Hatteras, off North Carolina. Combined wind and swell is never less than 3 feet off the West Coast and exceeds 12 feet almost a quarter of the time.

- While a large swell rarely causes more than discomfort (and involuntary feeding of the fish) in deep water, in shallow water it can produce dangerous breaking waves capable of capsizing even relatively big boats. So, when navigating in a swell, do not enter water shallower than two-and-a-half to three times the total swell height. (The easiest way to determine wave height is to consult the closest measuring buoy using NOAA's National Data Buoy Center and also available as an app.)

- U.S. Sailing investigated the loss of the Sidney 38 Low Speed Chase and the death of five of her crew in the 2012 Farallones Race, and found that the vessel crossed a 28-foot shoal with a forecast for swell of 12 to 15 feet and wind waves of 3 to 7 feet. In that depth, this combined sea and swell could produce a breaking wave capable of capsizing a 38-foot boat several times an hour. Be prudent and steer wide.

- When choosing an anchorage to weather extreme swells (in excess of 20 feet), look for protection from the swell direction and avoid anchoring in shallow water.

— The Editors