Advertisement

How to figure out what you need in your next boat, and where there's room for compromise — firsthand lessons from our technical editor, one of America's most experienced boaters.

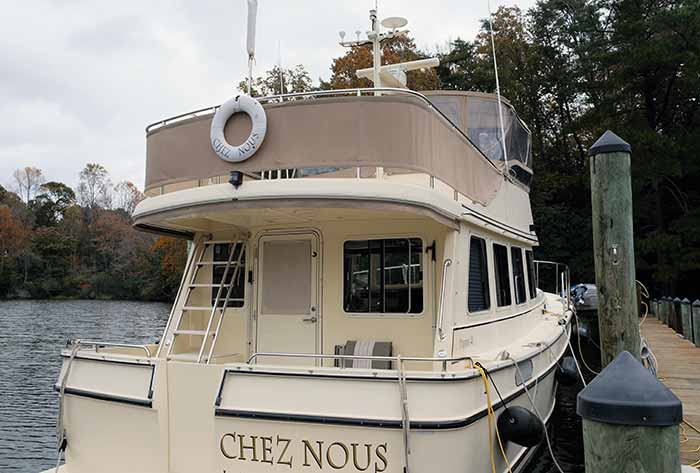

The latest Chez Nous is a 2006 Camano 41 trawler.

Mel and I didn't talk about it too much, but we both knew that this next boat also might be our last. We're "of a certain age" now, have grandkids, and want more creature comforts, more speed for safer passages, systems accessibility, stability, and a great environment for ourselves. What didn't we want? Another major renovation project or a boat with ancient systems needing constant care and feeding. Been there, done that. We started with a list of must-haves:

Fiberglass: It lasts forever, and there are all kinds of repairs you can do to a good fiberglass boat. I admired steel boats, having seen them survive on the reefs while fiberglass, aluminum, and wood boats shredded in minutes. But, in our opinion, rust is worse than blisters.

Tom enjoys the view from his new helm.

Mel and I didn't talk about it too much, but we both knew that this next boat also might be our last. We're "of a certain age" now, have grandkids, and want more creature comforts, more speed for safer passages, systems accessibility, stability, and a great environment for ourselves. What didn't we want? Another major renovation project or a boat with ancient systems needing constant care and feeding. Been there, done that. We started with a list of must-haves:

Fiberglass: It lasts forever, and there are all kinds of repairs you can do to a good fiberglass boat. I admired steel boats, having seen them survive on the reefs while fiberglass, aluminum, and wood boats shredded in minutes. But, in our opinion, rust is worse than blisters.

Solid construction: A deal-killer for us is any boat with balsa in the hull below the waterline. We preferred none in the hull at all. There are different methods for doing balsa, some far better than others. Vacuum-bagging, for example, can be successful if done well. But how do you know? Separation between the laminate and even high-quality coring can allow water to collect with perhaps serious consequences, especially when it freezes in the winter.

The hull "skin" is also important. A skin of polyester resin would be unacceptable because of the potential for blisters, unless well-treated. A hull skin of vinyl-ester resin would be acceptable. And, to protect the hull, we wanted substantial rubrails.

Hull-deck joints can seem a mystery. You usually can't see how it's done and don't know unless the builder tells you. A term I often heard in my professional Boat of the Year (BOTY) judging days was "screwed and glued." The builder places the deck onto a flange in the hull with (hopefully) a high-quality glue/sealant, then screws the two pieces together with stainless fasteners. This can be done with many variations and has proven a reasonably good method with many boats. But we wanted more: a layer of fiberglass cloth laid up inside the hull over the joint, making the hull and deck "one piece" and the entire structure tougher with little likelihood of separation and leakage in heavy seas.

Comfort: This means built to handle seas well and keep the rain out. It means air conditioning when you need it and showers when you're dirty, and sometimes when you're not, and so lots of water. It means room to store all your stuff, plus spares. In many boats today you see all the wide spaces and think: boy this is a comfortable boat. But when you look in the lockers they're only a few inches deep. Also, we didn't want to live in a tunnel. We did for a long time in sailboats. Someone would pull in and anchor and we'd all pop up out of the hatches to see what's going on above ground, like gophers. I wanted a flybridge.

Hull form: Mel and I use our boats to travel long distances. After years of sailboats, we wanted to be able to change scenery when the desire arose, or move fast to outrun weather. We wanted a fast trawler, but some of these have the same basic lines as slow trawlers, simply with more engine muscle. When you see these move at speed, you can tell that they're inefficient, poor performers. A boat built only for displacement speeds can have problems on plane, including instability while you're up, dangerous handing in following seas, a propensity for boarding seas or excessive spray, and excessive rolling. A hull has to be specially built to go slow well AND go fast well.

Systems accessibility: We wanted a boat that was easy to work. I was BOTY coordinator and a judge for Cruising World magazine for many years and fortunate to technically evaluate many fine boats. But one recurring observation was that some builders had little experience actually working on and repairing boats at sea. Often there were acres of flat screen but postage-stamp engine rooms.

I've seen gensets crammed into tiny crevices, and one beautiful boat with a 7 kW generator mounted over the propulsion diesel. You had to pull the generator to pull the valve cover! I've had boats with stuffing boxes 4 feet down in a narrow bilge. I've seen a raw-water pump where you had to remove the alternator and heat exchanger to change the impeller. No more shoehorn engine spaces for me.

An easy-to-work boat also means safe side decks and an expansive bow for working lines while docking and anchoring. I've been running twin- and single-screw boats for years, and have a fair idea of how to make them behave. But a thruster is a wonderful thing. A galley that has double sinks, a place to work, good stove, and storage is important but sometimes seem to be a design afterthought, like the biggest thing you're going to wash in the sink is a teacup.

Power: For ease of handling and redundancy, I thought I wanted twin engines despite the acreage they take up in the engine room. But with bow thrusters and an understanding of prop walk and throttle power, ease of handling is less an issue for me. Care and feeding of a good diesel makes it reliable, and with a single, you don't need two sets of spare parts. If you really need backup, there's TowBoatUS!

Tankage: Our wish list included tankage that was easily repairable and well-built of good materials. Too many boats need their hulls cut away if tanks leak.

Aesthetics: To us, practical is pretty. We love classic lines but not at the expense of a dry running hull, good living quarters, and storage. Maintaining teak lost its charm for us long ago.

Penny Wise, Pound Foolish

We've asked ourselves: What could we have done differently to avoid spending money in travel and surveys? The answer: Nothing. You must do thorough due diligence, including looking at the boat yourself and finding good surveyors. Some surveyors will do preliminary checks to help you evaluate whether you want to travel and hire them — very helpful.

Ask around. Often the seller's broker will recommend a surveyor he or she uses "all the time." However, it's wise to follow the advice of BoatUS Consumer Affairs, which is to be cautious using a surveyor recommended by a broker because of a potential conflict of interest. If you find a good surveyor, it's worth it to pay him/her to travel. Also, it helps to talk with other owners. Often you can find these on the internet in chat rooms and on owners' club sites. Take with a grain of salt anything you see on the internet, but you can learn a lot.

Kissing Some Frogs

Mel scoured the internet almost every day. Our daughter, Melanie, a yacht broker with Edwards Yacht Sales in Florida, sold our motorsailer. A hard-working professional, Melanie also knew what we wanted from her years of growing up onboard. Our searches proved frustrating. There were many inaccurate online listings and photos, or mistakes in the specs. Some brokers just cut and pasted from magazine articles, and sometimes when we called, they could give little info about the boat, like if it had a cored hull and other basics. In many cases, even the owners themselves weren't sure of basic boat information.

When we traveled to see a boat, involving time and expense, often what we found was unexpected. For instance, one boat that was incredibly well-built and designed had a flaw revealed at inspection: You couldn't see well over the prow from the forward window if you were up on plane, and she had no flying bridge. You could see at 8 knots, but we wanted to go faster.

Advertisement

Another boat had suffered damage to her bow rail, unbeknownst to the owner. He'd changed brokers, and they'd moved the boat to another brokerage location. This damage could have caused delamination in the hull, which was cored. Another boat looked very good from a distance but, when we traveled to visit, it had been used hard and put away wet.

On another occasion we made an offer that was accepted, started making arrangements for the survey, then found that while most of the boats of that model had foam coring, the first few had balsa below the waterline. If the builder of the boat you're interested in is still in business, contacting them can be invaluable.

We made an offer on another boat, and it was accepted. We spent several thousand dollars in surveys and travel expenses to check her out. She ran a little slow at wide-open throttle (WOT) — not necessarily a big deal, but concerning. When we hauled her, the surveyor, John Pepe from Oxford, Maryland, proved invaluable. He tested the hull by tapping it and using two moisture meters and an infrared sensor. He said he hoped he was wrong but thought it was wet. We had to know for sure. The owner drilled the cored hull and water ran out. The money we'd spent was gone — a risk you take.

The Camano 41: A Couples' Cruiser

Brad Miller had a successful 15 year career in Singapore, involved in venture capital and business startups. He had a little boating experience but nothing extensive and no boatbuilding experience. He and his wife, Jaslyn, decided to move and start a business in another part of the world that would be more of a service or lifestyle business with perhaps less stress. Boatbuilding wasn't on the list as they investigated several businesses and areas where they might want to settle. One area was the Pacific Northwest.

Brad was preparing to depart from Seattle after exhausting his search there when a broker called and suggested the Camano business, which was already well-established with a good reputation. He canceled his ticket, visited the plant, and later bought it. His first 31-foot Camano hull number was 78 and, all told, the company built more than 270. Soon after the 100th hull, he introduced molded liners to improve the hull interior and strength. When we met him in 2003, he was planning the Camano 41.

During a recent conversation, he told me that he began the Camano 41 project not based on boatbuilding tradition but from principles he had learned from building successful businesses. Know your market and build it well. He believed that the 31-foot hull would scale up successfully, but he hired a good naval architect to be sure.

He says that, for example, he didn't follow the traditional philosophy of "how many can she sleep?" He wanted to build for the couple who is going to be cruising by themselves. (This is what most of us do.) He made a concession to the occasional guest with a large comfortable fold-out sleeper sofa in the saloon and there is plenty of room for parties, but the forward stateroom, head, separate shower compartment, saloon and spacious galley are ideal for one couple. He avoided a raised pilothouse, thinking that most people, even on trips, are underway probably only around four to six hours a day. The rest of the time they want a large common area in which to live without that extra level. Yes, he had his market in mind. But he also had the "well done" part in mind.

The engine space was to have gelcoated surfaces to make cleaning oil and grit easy. He told me that he wanted a boat that, if you dropped a screw or tool, you would have no trouble finding it. (I can attest to that.) And taking it one giant step further, he said, "I wanted a boat in which every screw, nut, bolt, and fastener is where one can see it and get to it." This would be the boat for me. From what I can see, he met his goal. Brad sold the business after the seventh 41-footer when the world was in the throes of a bad recession. But he still becomes excited when he talks about the Camano 41. It's obvious he still loves these boats.

Finally, A Boat Appears!

One morning in June 2018, Mel checked her computer and found a 2006 Camano 41 new on the market. All the homework and reading we'd done indicated that this could be a good boat for us. Approximately 270 Camano 31s had been built in the Pacific Northwest, and we'd never heard of an owner who didn't love them. Some years ago, while associated with PassageMaker magazine, Mel and I helped lead a "Pokey Run" to the Bahamas with many 31s in the fleet. There we met the Millers who were building the 31s and planning to introduce the larger 41. The hull form was tried and true and gave special attention to well-planned systems, design, layout, practicality, and sea-kindliness.

She had a fairly fine entry bow but quickly flattened aft to give lift. Her bow above water was flared to shoulder aside seas, and her propeller was protected by a skeg. Within the Kevlar and fiberglass is a stainless-steel plate, serving as an extra reinforcement for stress areas in the stern. Forward of the skeg was a hollow keel, providing stability and buoyancy to climb to a plane.

We watched a video of Brad Miller running his first 41 at WOT as he put the wheel hard over. She barely noticed it. Her hull form and single 465-hp Yanmar kept her tight to her lines. This wasn't just a displacement hull that would get it up on plane with huge extra muscle. It was a hull designed to run either way. And she had three very tough rubrails!

Mel lovingly removes the name Chez Nous from the stern of our 53-foot motorsailer, which had been our home for 19 years. We've had the name since 1969, spanning four boats. The Camano is the fifth of the line. And, yes, the new lettering came from BoatUS Boat Graphics. (Photo: Tom Neale)

Of course, there were compromises. This one had a deck that was less wide than what we preferred as we walked forward, and it didn't have a high bulwark guarding the deck from the drop of the hull. But she did have sturdy, well-placed handholds and good width in the saloon. She had one engine so didn't go the 30 knots I wanted, only 16 or 17. But then Mel said I'd be crazy to go 30 knots anyway. The boat had more draft than we wanted, but at just under 4 feet, it had that skeg-protected prop. She didn't have as much fuel and water capacity as I wanted. But 385 gallons of fuel and almost 200 of water was enough. It had coring in the hull but — good news — it was Corecell foam above the waterline. It had solid fiberglass with vinyl-ester resin reinforced with carbon fiber below the waterline and a huge reinforcing molded liner structure glassed onto the inside of the hull to support the engine and other components in the engine space as well as throughout the boat.

She was built in 2006 but because of the recession remained unsold until 2008. The first owner kept her in Great Lakes freshwater. She then came south to her present owners who had already done the loop in a Camano 31. Our daughter, Melanie, called the Camano's broker, Doug Ford of Intracoastal Yacht Sales in Little River, South Carolina. The boat was in passage not far from where we live and scheduled to come to a nearby marina for weather. We made arrangements to meet her owners and see the boat. You can tell a lot about a boat by her owners; these were special people who loved their boat.

One of the first things I noticed as I viewed the engine space on the boat was just that — the abundant space. The second thing I noticed was the hatch in each fuel tank that could allow entry and repair. We came back the next day, had tentative discussions to buy her, and made a formal offer the following day. She proceeded on to Little River where the owners wanted to leave her to sell.

No matter how much you think you know about boats and what you want, a good surveyor is critical, as we'd learned in Maryland. We used Michael Hagan of CYA Maritime Services in Jacksonville, Florida. At one point I saw him sitting on the closed lid of the toilet, wiggling around. "The potty test," he said. "Sometimes these things aren't bolted down well." He was excellent and never stopped exploring and scrutinizing during the entire 10-hour day he was aboard.

Taking Delivery

Because of our schedule, we thought we wouldn't be able to bring her home ourselves. We wanted to have the boat in the Chesapeake as soon as possible — Hurricane Florence would roar ashore nearby a few weeks later. Doug recommended hiring an experienced captain who knew the trip. As it turned out, I was able to make the trip but hired Nick Smith anyway so I could spend time learning the boat rather than running buoys. It was a good decision, and he did a great job.

We made it from Little River to the Hampton Yacht Club in Virginia in just two and a half days — a record for me. This was my home club. When I ambled ashore, I ran into my old friend Chris Hall, chairman of Bluewater Yachts, and his wife, Judy. Chris had sold us our first cruising sailboat around 50 years ago — our first Chez Nous. We and a few other friends shared some good laughs over old memories and a beer or two. I had a boat again and was back in my native Chesapeake Bay. As Robert Earl Keen sang, "It feels so good feelin' good again."