Advertisement

Besides knowing a boat's age and engine hours, here's what you need to consider before refitting or restoring a fiberglass boat, including boat type and usage, hull construction, structural problems and mechanical damage.

The refit or restoration of an old boat is one of those endeavors that appear to have no practical value but can be very satisfying emotionally to the appreciative eye. Everyone takes notice of a gleaming mahogany runabout or gaff-rigged wooden sloop that typifies the world of antique and classic boats. Nonetheless, fiberglass has been around for over 50 years and has become the recreational boatbuilder's material of choice. Now that some are old enough to qualify as "classics," older glass boats sporting impeccable urethane paint jobs are beginning to get their share of the "oohs" and "aahs."

Despite the fact that wooden boat restorers wear their heroic mantle proudly and snort at the notion that an old glass hull could present serious refit obstructions, in comparison to fiberglass, the nature of wood construction simplifies hull repairs. Wood hulls may be made from biodegradable materials but at least they have replaceable parts. The restoration of a wood hull can be carried out one plank or rib at a time. If the ongoing replacement of degraded parts is carried out diligently, there is no theoretical upper time limit to how long a wood boat will last.

Unfortunately, a fiberglass hull is practically monolithic, a "one-shot" deal, and if the hull is just plain tuckered out, what can you do? There are a few options for structurally repairing the whole hull but none of them are easy and may make a refit impractical. Like wood, glass hulls are not immune to the forces of nature, but here it is not biology but chemistry and physics working against them.

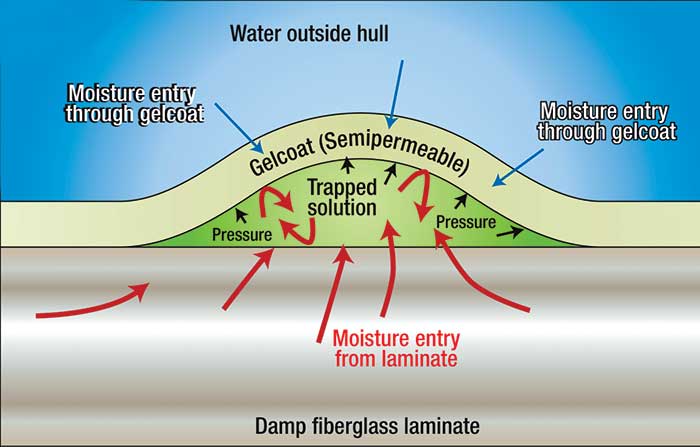

Cross section of a typical fiberglass osmosis blister.

The two destructive agents at work on a glass laminate are: moisture, which can attack resin or seep into cored laminates, and flexing, which not only breaks individual glass fibers but also causes layers of glass or core to de-bond and separate, an evil known as "delamination."

Blisters Casebook

Once upon a time people thought fiberglass hulls were inert in contact with water. Glass fibers are, but over time some polyester resins proved to be surprisingly soluble. Water molecules penetrate into a susceptible laminate by seeping through the gelcoat and wicking along the glass fibers. Once in contact with the resin, the water can react with soluble polyester components (mostly glycols and dibasic acids that are not fully bound or cross-linked into the polyester), a process known as hydrolysis.

The hydrolytic process picks apart the polyester molecules and the resin begins to leach away. A microscopic droplet of leachate solution (consisting of water and those pesky polyester components) collects in one of the tiny voids or air bubbles that exist in all glass laminates. Additional moisture is drawn in by osmotic action, the droplet grows and eventually a blister forms.

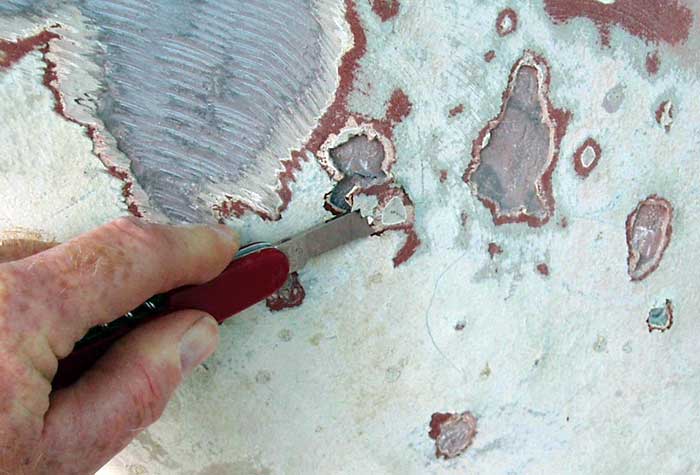

The pox-like signs of osmosis show hydrolysis is at work. Time for a barrier coat before things get worse.

As the process continues, the hull develops a classic case of osmosis blisters. A minor case of blisters is a cosmetic problem and affects only the gelcoat. A severe case forms big blisters deep inside the laminate, which can lead to major hull delamination and weaken the hull to the point of being unseaworthy.

Blisters can be repaired but the cost is high and the prognosis iffy. The conventional blister repair technique of drying the hull, removing the gelcoat and, in the worst cases, layers of leached laminate, finally re-skinning the boat with new laminate and/or an epoxy or vinylester barrier coating usually works.

This traditional repair strategy does not correct any problems with the fundamental resin chemistry but concentrates on repairing the existing damage and denying moisture access to the laminate from the outside. Moisture can still get into a susceptible laminate from inside the boat via condensation, bilge water, etc. and, unfortunately, there are hard cases out there that refuse to stop blistering even after a good conventional repair.

Core Contents

Cored hulls can suffer from hydrolysis and the resulting osmosis blisters can exacerbate a far more dramatic problem resulting from poor workmanship or abuse. If the core lay-up is not well sealed during construction and/or someone drills a hole for an aftermarket thru-hull below the waterline and does not seal it properly using the potting technique, water will seep into the core. It may take years on a quality hull to saturate a significant area.

Blister analysis requires a sample to examine.

As the process continues, the hull develops a classic case of osmosis blisters. A minor case of blisters is a cosmetic problem and affects only the gelcoat. A severe case forms big blisters deep inside the laminate, which can lead to major hull delamination and weaken the hull to the point of being unseaworthy.

In cold climates, the process is accelerated by frost heaving that can debond the core from the inner or outer glass skin. However, some tests have shown it takes a very wet core to be susceptible to freeze damage, in which case the boat is not a good candidate for fixing up.

All core materials are degraded by water absorption but balsa wood core is particularly vulnerable to long-term saturation. If caught early, while the balsa is still sound, it may be possible to dry the core, otherwise major surgery is required. This involves removing either the inner or outer skin, digging out and replacing the old core material and re-skinning the repair area. Depending on the extent of the problem and the quality of the boat, this sort of repair can be more expensive than a blister repair but on a great boat may still be worth doing.

Hull Flexing

The other great killer of fiberglass hulls is flex (stress). Motorboat hulls take a constant beating and are built as lightly as possible to encourage quick planing. Over the years, the mechanical characteristics of the hull laminate degrade as each wave impact (or pothole encountered while trailering) bends the laminate and breaks another tiny glass fiber or knocks it loose from the grip of the resin.

Gradually, the hull loses stiffness and becomes more flexible. Stress cracks appear at stringers, bulkheads and running strakes. Eventually, delamination occurs as the bond holding the individual laminate layers together fails.

A delaminated powerboat hull won't survive long in normal service. Major cracks extending deep into the laminate will soon appear and with them the risk of a catastrophic hull failure. This usually occurs when the edge of an athwartship crack snags the high-speed water flow on the bottom and a piece of the hull is instantly peeled back. When this happens, you are lucky if the missing chunk is just an outer layer of a multi-layer laminate.

Sailboats can also suffer from accumulated mechanical damage inflicted by years of use and abuse. Everything from bashing through a short chop on the way to a weather mark to improper cradling can contribute to a global loss of stiffness in a hull and eventually to areas of delamination.

Mechanical damage to hull laminates can be repaired but can be a daunting job, technically and financially. It's just a matter of grinding out delaminated areas and laying in new fiberglass, plus filling and fairing. If the whole hull is tired — in other words, just too flexible throughout — you are faced with a job that is equivalent to building a new hull using the old one as a male mold.

Selecting a Refit Candidate

So, it seems that a fiberglass hull can slowly dissolve and/or get beaten to death. Is this the fate that awaits them all? If so, when? No one really knows how long a glass hull will last. It all depends on an almost infinite number of variables and the answer will be different for each boat.

If you are planning to refit any glass boat, it should be surveyed carefully. You need to make an educated guess about the hull longevity of your potential refit candidate before going to all that time and expense. Hire a surveyor to help with this assessment.

They don't build them like this anymore with 2"- (5cm) thick solid glass!

Despite the fact that glass hulls vary widely, you can make some educated calculations based on the following factors. First are the quality and type of original construction. Generally thicker and heavier eventually to areas of delamination. Mechanical damage to hull laminates can be repaired but can be a daunting job, technically and financially. It's just a matter is better than thinner and lighter. Many early glass boats were built to the same thickness as their wood predecessors. Other than hydrolysis and blister issues, not much goes wrong with these old heavy hulls.

A hull from a high-end builder will usually last longer than one from a budget boatbuilder. Everything else being equal, you get what you pay for. High-quality cored construction (if properly maintained) is much stiffer than solid glass of the same weight and can hold up very well in the long term, provided the core stays dry.

Second are the boat's age, hours, history of use (or abuse) and maintenance experience. A boat that was hauled periodically will be less waterlogged and less prone to osmosis; likewise for a boat with a good barrier coating. Beware of planing powerboats with high hours and that are pre-1980s vintage. Avoid all planing powerboats coming out of commercial, police or military service.

Even a high-quality hull can be thrashed in a few years by 2,000 hours of service annually. It would take an enthusiastic weekend boater five to 20 years (depending on the latitude) to put those hours on a hull.

Lastly is the type of boat: power versus sail, high speed versus moderate speed. There are always exceptions but generally, cruising sailboats and displacement powerboats age better than lightweight racing sailboats and planing powerboats.

Any glass hull can be repaired and renewed. It's just a question of whether it's worth it to do so. If Nelson's HMS Victory or the USS Constitution had been built of fiberglass, I'm sure ways and means would be found to carry out the necessary repairs today. Some boats deserve to live forever, be they wood or glass.