Advertisement

One moment you're enjoying a day on the water. The next, you need help. Here's what to do when you call for a tow.

Calling for a tow doesn't need to ruin your day, especially if you're prepared.

BoatUS handled more than 50,000 dispatches in 2013, the vast majority of which were garden-variety tows — dead batteries, empty fuel tanks, soft groundings, and the like. If you ever have to call for a tow, it's much more likely to turn out to be a long, boring afternoon than a dramatic salvage or life-threatening situation. According to Capt. Dale Plummer, who operates TowBoatUS Baltimore/Middle River, most tows consist of 10 steps. Knowing what to expect if you ever have to be towed will help make the experience as simple and trouble-free as possible.

1. Calling For Assistance

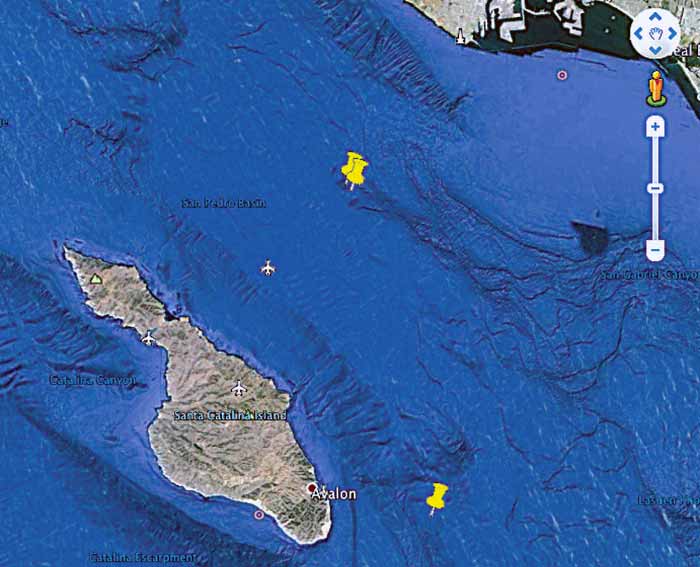

Whether you request a tow by phone or radio, know where you are. "It's frustrating when someone says they're off the smokestacks south of Baltimore," Plummer says. Not only are there more than one set of smokestacks, most people can't judge distance well. Even if your boat is not equipped with GPS, your smartphone can give your position (see sidebar), and that will get a towboat to you faster. The BoatUS Towing App is even better, automatically providing your position to the dispatcher when you call for a tow.

2. Agreeing To Fees

The first question a dispatcher or towboat captain will ask is if you have a prepaid towing service. If you have to pay some of the costs yourself, TowBoatUS captains will provide you with an estimate, on a per-hour basis, that includes the time from the operator's dock to your location. "Out-of-pocket costs for a tow start at about $200 an hour here," Plummer said, "with an average tow costing about $700 per incident." Hourly charges increase after dark or during small-craft warnings. Why so much? Many towboat operators own and maintain several boats, and pay multiple captains to make sure one will be available 24/7. "The worst part of my job is when I have to hand someone a bill who doesn't have a towing package," Plummer said.

Tip

Keep a copy of your insurance and towing service information in a waterproof place somewhere on the boat, and make sure anyone who might use your boat knows where it is.

3. Establishing Communications

Once contact is established, and fees have been agreed upon, the towboat captain will tell you how long it will take to reach you and set up a way to communicate. The captain may ask for more details to identify your boat. If you're under sail and want to make headway toward your destination, establish a rendezvous point and ETA. Don't be afraid to check in with the tow company. "More communication is better than less, especially if the situation changes," Plummer said. "And after calling for a tow, please answer phone calls from unrecognized callers. It's probably the towboat captain trying to make contact."

4. Preparing For The Tow

In case the wait is long, in an effort to move things along once the towboat arrives, setting up lines and fenders may seem like a good idea. But the towboat captain will use specialty lines and, if needed, fenders, and will determine the appropriate attachment points, which may not be those you'd expect. "You can get your lines and fenders out and have them ready to deploy when you're approaching the dock," Plummer said, "but keep all cleats free of lines and the boat's sides clear of fenders until the captain tells you otherwise."

On the other hand, if you're on a sailboat, the towboat captain will ask that sails be lowered and flaked before passing you a towline. Having them down when the towboat arrives will make your boat easier to pick out and save time; however, only do so if there's no chance you'll need the sails to maneuver before the towboat is on scene.

5. Attaching A Towline

The towboat captain will explain how he wants to get a line onto your boat. For trailerable boats, Plummer uses a long gaff to attach a quick-release shackle to the bow eye down near the waterline. He passes a line with a spliced-in loop to larger powerboats. This needs to be taken through a fairlead and to a cleat, and the loop dropped over the cleat. "Don't use a cleat hitch or tie the towline," he says. "You need to be able to release it quickly if there is a problem." Plummer uses a bridle with spliced-in loops for sailboats to ensure they track in a straight line while under tow. The loops need to be led to the bow cleats in such a way that they won't chafe. "Anchors often interfere with the bridle on sailboats," Plummer says, "so it may be necessary to remove them for the tow."

6. If It Becomes Salvage

Once in awhile, a garden-variety tow can turn into salvage. That could happen if, for example, a violent thunderstorm suddenly puts the boat in peril of being swept ashore, or if a falling tide turns a soft grounding into a hard grounding. In that case, TowBoatUS operators are required to let the boat owner know, if there is any way to do so, that the situation has changed. Salvage will be far more expensive than towing. Towing service agreements don't provide for salvage; insurance policies do (check in advance as not all policies provide full coverage for salvage). So let your insurance company negotiate the salvage with the towing company.

7. Towing Astern

For most of the tow, your boat will be pulled well astern of the towboat, in the smooth part of the wake. You'll stay aboard the boat to make sure nothing goes wrong. The towboat captain will tell you what to do with the helm. In most cases, the helm should be centered. Stay seated. Don't try to steer. Before getting underway, you and the tow captain will agree on how to communicate, most often on a designated VHF channel. If the tow takes a long time, be sure to check in occasionally. "Towing at night, especially in rough conditions," Plummer said, "I worry someone may go overboard, so I appreciate them staying in touch."

8. Towing "On The Hip"

To maneuver in the close quarters of a marina, your boat will need to be brought alongside the towboat, or put "on the hip," so the two boats operate as one. While you're still well outside the marina and its traffic, the towboat captain will slow, then stop before pulling your boat up close. Exactly how the two boats will be secured will depend on the relative size of the boats, wind/current speed and direction, which side the dock will be on, and how much room there is to maneuver. The towboat captain will provide both lines and fenders for this operation, so once again, keep your boat's cleats and sides clear.

9. Readying To Tie Up

Once your boat is positioned "on the hip," and the towboat captain is heading into the marina, go ahead and put lines and fenders on the side opposite the towboat. You can set up lines and fenders for the side the towboat is on, but you'll have to wait until your boat is free to put them in place.

10. Entering The Slip

A good towboat captain will be able to ease you right into your slip, but the operation is a delicate one that can be disrupted by snubbing off a line or pulling the boat hard into the dock. Stay aboard the boat and wait for the towboat captain to tell you to tie off before doing so. The towboat captain will remove the towline, you'll agree on how the charges will be settled, and your boating adventure will be over — at least for today.

How To Relay Your GPS Coordinates Accurately

If you ever need a tow, the first order of business will be telling the dispatcher where you are. If you have a GPS aboard, read your latitude and longitude (lat/lon) off the display. If you have cell coverage, you can probably get your position off your phone. On an iPhone, activate your compass app; your position will be at the bottom. If you have an Android, download an app first or learn how to get your lat/lon from Google maps. If you have the BoatUS App, your position will be right there when you open it up. Simple, right?

There's one more thing. There are multiple ways your position may be shown on whatever device you use. If you don't communicate your position correctly, whoever comes to help might end up too far away to actually find you. BoatUS TowBoatUS Captain Paul Griswold relates a story about a call that came in to the Newport Beach, California, towing port last summer. "Dispatch assumed the five digits after the degrees were minutes and decimal minutes. But it turned out the phone was set to degrees and decimal degrees, which put the position off by about 10 miles." Fortunately, the boater was found before dark. But this small miscommunication could have had grave consequences.

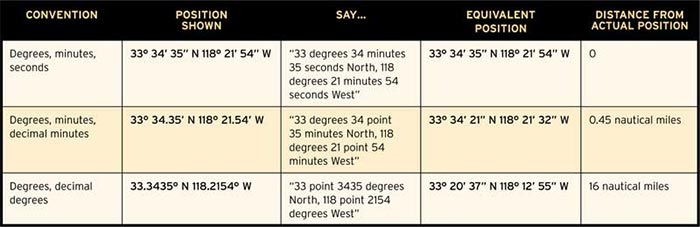

Traditionally, positions have been reported in degrees, minutes, and seconds, with 60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in a degree, and one degree of latitude equal to approximately 60 nautical miles. That means one minute is equal to about 1 nautical mile (about 1.2 statute miles). Computing with this convention is like trying to do computations with time — slow and cumbersome given that we're all used to the convenience of decimal notation. Computations in computer-based systems are also faster using decimals, and the underlying data used by our devices is almost always in degrees and decimal degrees. So 33° 34' means 33 degrees and 34/60 of a degree, while 33.34° means 33 degrees and 34/100 of a degree. That's a difference of about 0.2 degrees or 13.6 nautical miles (16.3 statute miles). The table below illustrates these differences and how to communicate each convention accurately. The iTouch website lets you play with these conversions and find the position for any point on a world map.

Finally, the best way to transmit your position in an emergency is to connect your DSC-enabled VHF to your chartplotter or GPS so that the radio can relay your position when you push the distress button. The U.S. Coast Guard estimates that 80 percent of DSC radios aren't connected to a source of position data. There are now VHF radios with built-in GPS that eliminate the need for a connection to your plotter. Until recently, only handheld models were available. But this spring, Standard-Horizon released a fixed-mount model, the GX1700, for less than $300.