Advertisement

Improve your anchor’s performance with a kellet, star mooring, anchor riding sail, and more.

Illustration: At ease while anchoring

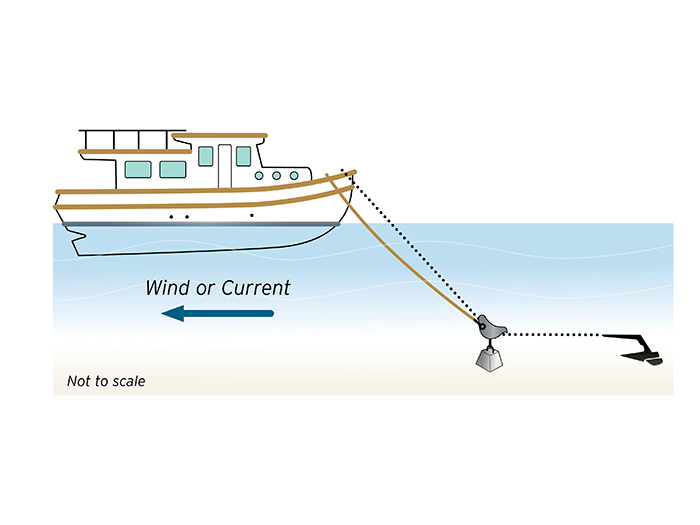

At ease while anchoring with a kellet approximately halfway down the anchor rode There are additional advanced anchoring tricks to improve your boat’s performance while anchored that have nothing to do with the anchor itself. One is using a kellet (also known as an “angel” or “sentinel”), which is simply a weight sent down the rode once the anchor is set, to steepen its entry angle and decrease the anchor’s lead angle on the bottom.

A kellet can be useful in many situations, such as when dragging anchor in an anchorage that’s too crowded to make paying out additional rode a viable option. A kellet should weigh between 25 to 35 pounds for a typical 35-foot vessel, but this can be increased in heavy weather to generate additional holding power. The kellet should typically be positioned along the rode halfway between the bow and anchor, however this distance can be varied to compensate for local conditions. For example, placing it farther up increases the shock-absorbing qualities of your rig, while lowering it closer to the anchor increases holding power. The kellet retrieval line should be attached to a bow deck cleat and kept fairly taut, to reduce chances of it fouling. Use chafing gear where needed.

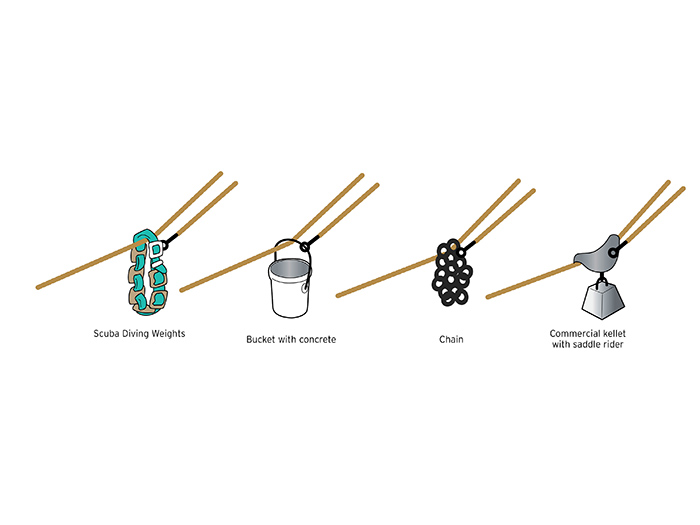

Illustration: Kellet Types

You can buy a kellet or make one from materials at hand, such as scuba diving weights, a weighted canvas bag, or even a small anchor. It can also be constructed from a 1- to 2-foot section of large diameter PVC pipe capped at both ends and filled with lead or chain. A large shackle can be used as a rider for the kellet on all-chain rode. Combination rodes require the use of a saddle rider, snatch block, or other suitable means of attaching the kellet to prevent chafe.

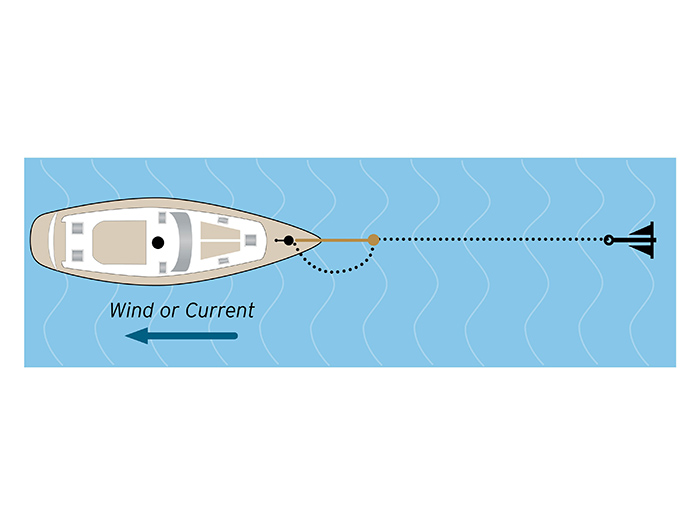

Another common problem while on the hook is “anchor sailing” or sheering, caused by windage from a boat’s hull, superstructure, and rigging. With each wind shift, the bow falls away from the wind only to be brought up short by the anchor rode, which in turn forces it to point in the opposite direction. Sheering is more pronounced in modern boats with wide beams and narrow keels, but any vessel riding to a single anchor is susceptible. Sheering is annoying and potentially dangerous due to the excessive side loads it places on ground tackle, which could lead to dragging or failure.

Illustration: Bridle and Rolling Hitch

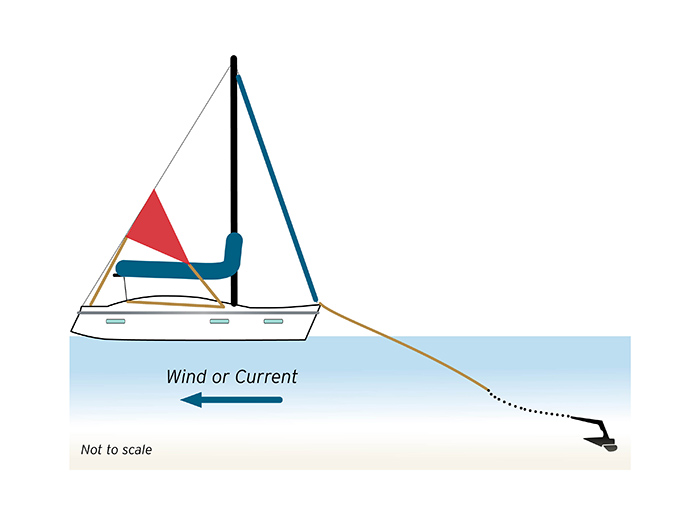

Illustration: Anchor Riding Sail

Illustration: Anchor Chain Loop, Credit Mel Neale

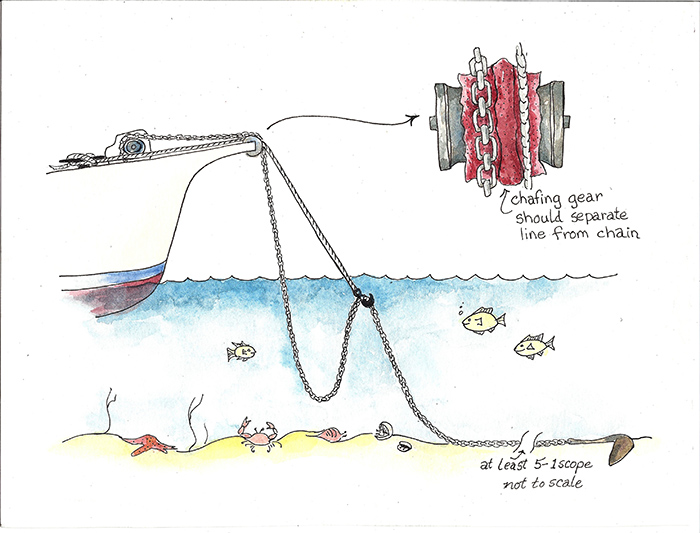

Chain Loop Method

Many prefer the chain loop method, as depicted here, to using a kellet. The weight and mass of the chain provides a similar benefit. You can increase or decrease the weight by letting chain out (as long as it isn’t sitting on the bottom) or by pulling it in. The loop also provides anti-sailing drag. The nylon snubbing line, which many attach to the chain with a rolling hitch or hook, can also be let out or shortened from the deck as need arises. This line adds elasticity to the rig and enhances the rig’s catenary effect, lowering the pull on the anchor. Chafing gear should be used, but if the rope wears through, it can be replaced – even in a blow – by deploying more chain.

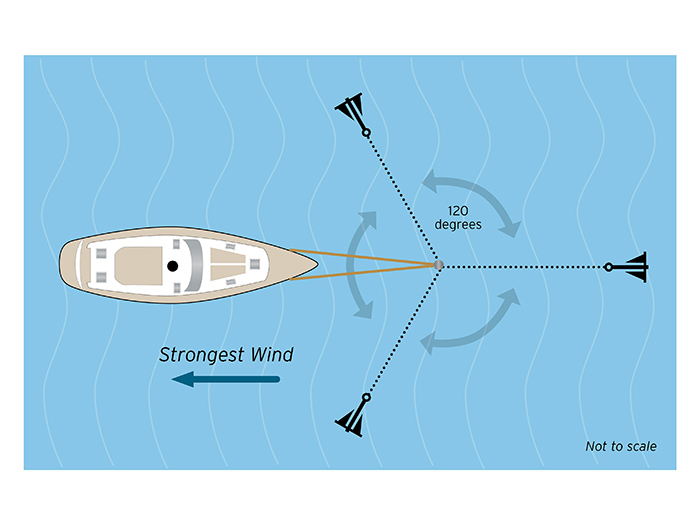

Illustration: Modified Star Mooring

Modified Star Mooring

The versatility of a star mooring (coupled with the holding power of kellet, if required) is hard to beat. In this type of mooring, three separate anchors and rodes are laid out 120 degrees apart, with the largest anchor set toward the direction of strongest expected wind.

The three anchors can have all-chain rodes or be a mix of chain rodes and combination rodes (i.e., rope and chain). Once deployed, each of these are then shackled in the center to a large shackle or mooring swivel, which is in turn shackled to a bridle of 3/4-inch three-strand nylon or larger (depending on boat size), which is then attached to your boat. If used, the kellet is attached directly to the large shackle or mooring swivel, as appropriate, using a short length of chain or line.

The two lines of the bridle (which will ideally have a galvanized thimble spliced at the end shackled to the mooring swivel) should be 10 to 15 feet longer than initially required, with the extra length secured on deck. This allows you to increase scope or shift lines as necessary to prevent chafe at chocks or hawseholes.

Colligo Marine’s five-line star swivel is not available for sale on the company’s website, but it will manufacture them on request (colligomarine.com).

A variation of the above would be eliminating the mooring swivel and bringing each of the three rodes to one side of the vessel at a single point, then forming a bridle by attaching another line via a rolling hitch or other secure attachment to the three at the juncture where the swivel would be in the above example, ensuring adequate chafe protection is provided. Some feel that a swivel may provide a weak link in your rig. This must be a matter of your judgment, on-the-scene assessment, and equipment.

The addition of a heavier-than-normal kellet (50 to 60 pounds) to the center of the mooring adds even greater holding power, while reducing the vessel’s swing radius and anchor sailing if you need to pay out more scope on the bridle.

Take storm surges and higher than normal tide levels into consideration when determining how long your bridle and anchor rodes should be. If your anchorage is 15 feet deep (normal high tide) and a storm is due to hit at high tide with a predicted surge of 10 feet, then your bridle lines should be at least 45 feet in length – 15 feet for the anchorage’s normal depth, 5 feet for trapped high tide, 10 feet for the surge, plus the extra 15 feet of reserve line on deck mentioned above. Just remember that this is for the bridle length only – not the anchor rode.

Based on a scope of 7:1 for normal anchoring and a projected maximum depth (of the above anchorage) at 30 feet, each of the three anchor rodes in the above scenario would need to be 210 feet. However, this can be rounded down to 200 feet as the pull of the boat will almost always be divided between two of the three anchors.

Finally, be sure to provide plenty of chafe protection at all chocks and fairleads that the bridle or any anchor rode contacts, and mouse (secure) all screw pin shackle pins with stainless steel wire to prevent them from unscrewing.

Learn more about anchors and anchoring.