Advertisement

He'd never been on a boat before and hardly knew anything like Sans Souci existed, that is until he saw her, and it would change his life.

Illustration: Mary Ann Smith

I was 9 when I first took the wheel of a boat — a slim, plum-stemmed wooden cruiser named Sans Souci. The 40-foot Consolidated commuter yacht was built in 1935 and belonged to a man everyone called "The Judge," a big Irish fellow fond of cigars and beer. The occasion that day more than 50 years ago was a birthday fishing trip for The Judge's first-born son, a childhood friend of mine. But The Judge hardly needed a reason to take out Sans Souci. Between late March and Thanksgiving, if he wasn't wearing his magistrate's robe or hemmed in by duties at home, he was aboard his beloved boat.

So despite the sorry spring weather — raw, cloudy, cold — we set out from Bay Shore's Watchogue Creek for Great South Bay on the south shore of New York's Long Island. The screws churned slowly, gently pushing the old girl through the waves, a thin apron of foam spreading at her bow. It was my first time on the bay, and as I stood in the cockpit watching things on shore grow smaller, we may as well have been bound for the open sea instead of across the bay toward Dickerson Channel and the marshes of Captree.

I'd never been on a boat before and hardly knew anything like Sans Souci existed. The varnished wheelhouse, worn down by time, with its brass hardware and seat cushions covered in turquoise Naugahyde, glowed with the wonder of a fortune teller's booth. Below, like many vessels of her time, Sans Souci sported bronze ports, whitewashed bulkheads, and narrow bunks. Stout knees, thick ribs, and heavy scantlings, all painted white, peeked out from under the gunwales, where tools, hats, and books were crammed into cubbies. On deck a fine green verdigris graced her hardware, except where busy hands and lines kept the bronze polished a deep brown. I knew nothing of boats or the sea, but everything about her spoke to me. I fell under a kind of spell.

My father had served in the Navy before I was born, but otherwise my family had nothing to do with boats. Nothing in my life predisposed me to feel what I felt stepping aboard Sans Souci. My emotions were a jumble, but a child hardly understands half of what he feels.

Though The Judge is long gone and Sans Souci sadly scuttled 25 years ago when are days I still marvel that I ever chanced to step aboard her. I only have to row by Sans Souci's old slip, close by where I've kept a small sloop docked for years, and I'm back on board, watching her wake unfurl on a slate-colored sea. I was lucky. One of destiny's little darts struck me that day.

A Strange New World

When we reached the other side of the bay, The Judge throttled the engines back, slowed Sans Souci to a crawl, and turned her into the wind. Then he put both engines in neutral and went forward to drop the hook. Returning to the wheelhouse, he backed the boat down to make sure the anchor bit. Satisfied, he idled the engines lower with ceremonious care, listening to them like a doctor listens to someone's heart, before shutting them off.

I knew nothing of boats, but everything about her spoke to me. I fell under a kind of spell.

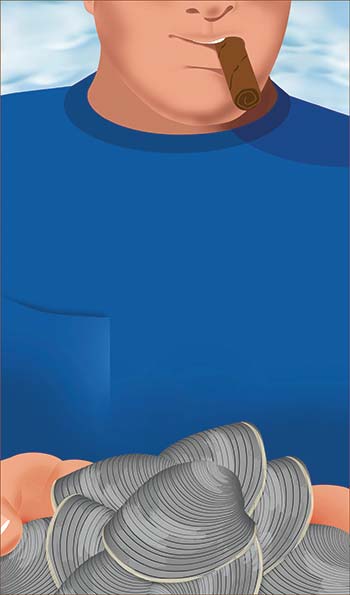

With the boat resting easy in Captree's lee, The Judge picked up a pair of clam tongs and spent the next 10 minutes digging quahogs from under the boat. When he had a couple dozen, he gathered the clams onto a wooden board used for cutting bait, pried one open with a dull, big-handled knife, then sucked the whole clam off the shell and swallowed it. Approving of the taste, he opened the rest, tossing the pale meat into a milk carton filled with saltwater. Then he handed us our rods and opened up a beer.

Illustration: Mary Ann Smith

I followed my friend's lead, picking through the slippery mess for bits of clam big enough to stick on our hooks without sticking ourselves, though our hands were so numb by the cold we hardly felt it when we did. Now and then our reels spun out bird nests of cotton line when we forgot to slow the spools with our thumbs. The Judge would then fetch us another rod while he undid the tangle. Impatient fishermen, we jerked our rods impulsively whenever something tugged at our lines, reeling them in to see what, if anything, we'd caught. Crabs let go at the surface, but whatever we'd hooked got hauled in flapping over the side.

For the most part, the bay bottom is home to creatures no one wants to meet, like spider crabs and eels. The uglier the fish, the harder it is to get off the hook — sea robins and eels count among the worst. Eels snap like nasty dogs and are so slippery you can hardly hold them down with your foot. The Judge, used to wielding a gavel, dispatched the eels with a blow from a wooden mallet. Then, because eels make good barbecue, he worked the hooks out from behind their teeth and tossed them into an old creel. Sea robins were another story. Mostly mouth and spines, it's near impossible to handle one without getting pricked. They swallow the hook so deep sometimes you can't get it loose without pulling the fish's insides clean out. Like any kind of hand-to-hand combat, it's a contest best avoided. So when it came to sea robins, The Judge would just swear, snip the leader, and throw it far downwind of the transom before tying a new hook on for us and going back to his beer.

Advertisement

The flounder is a pleasant exception among bottom denizens. Small mouthed, docile, easy to catch, it's a veritable fillet with fins. That afternoon, we caught our share of flounder, along with several eels and a handful of sea robins. When the flounder filled most of a 3-gallon pail, The Judge declared it time to head home and ordered us to reel in our lines. With as much ceremony as he'd shut each of them down, The Judge started up one engine, then the other, then went forward and retrieved the anchor, returning to the wheelhouse with wet pants knees.

Homeward Bound

A few minutes later, Sans Souci began cutting her way through the chop as we motored out from under Captree's lee. The Judge, a well-bit cigar between his teeth, held the wheel with one hand while tapping the throttles back and forth with his other, attending to the dutiful diesels beneath his feet, trying to bring them into sync by ear, to find the speed at which the old girl waltzed happily with the seas. Toward the middle of the bay, the water deepened and the warrantless wind blew. Unruly white caps rose up and chased us, but Sans Souci ran from them, throwing her skirt up in play sometimes when they spent themselves in her wake.

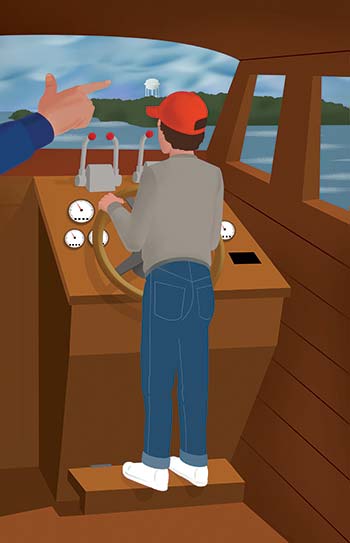

Sitting on a bench just inside the wheelhouse, I was looking out over the transom, watching the marshes fade, when The Judge called my name. I turned, and he stepped away from the helm, waving me over. He'd built a fold-down step beneath the wheel for his kids to stand on and steer. Kicking it down with his foot, he instructed me to stand on it and take the helm. Perched there, my hands gripping the wheel, I looked out over the long bow at a shadowy sea splashed with foam. The Judge pointed toward a water tower a few miles away. "Steer for that," he said, and then, as if trusting a 40-foot boat to a kid were the most natural thing in the world, turned and headed toward the stern and cutting board.

The tower was little more than a gray thumbprint above the distant shore. Afraid I'd never find it again if I let my vision stray, I kept my eyes on it. Now and then the boat rolled hard or dug her bow and yawed, and I'd sometimes lose sight of the tower. Each time that happened, I scanned the shore anxiously, grateful a helmsman as ever lived when I saw the mark again.

[The Judge] gathered the clams onto a wooden board used for cutting bait, pried one open with a dull, big-handled knife, then sucked the whole clam off the shell and swallowed it.

Illustration: Mary Ann Smith

The whole time I was steering, I could hear The Judge's knife against the cutting board, as one flounder after another lost its head and guts to the gulls who'd been eyeing our bait all afternoon. The birds fought rudely for the bloody scraps he tossed overboard, their cries sometimes drowning out the swish of the hull as it surfed down the crests. When the gulls came in close to make a play for his fillets, The Judge cursed the birds roundly and waved his knife above him in the air. Soon enough the work was done, the fillets wrapped in wax paper and packed inside the cooler with what remained of The Judge's beer. The gulls' harried calls grew increasingly plaintive. One by one they disappeared, and the seas settled down. I clung less tightly to the wheel, swaying freely when the boat rolled or pushed a wave aside. I'd gotten my sea legs. Closing in on Bay Shore, which in a few years would become my new home, The Judge relieved me of the helm, and I stepped out into the cockpit.

If my first time on the sea's doorstep was a raw, dismal day, the sky a shadowy tumble of clouds, I've never wished it otherwise. Some days the sun spreads a diamond shawl upon the sea's shoulders, but on others the sea is full of bitter spirits, and it's better to taste them early than late. Too young to know it then, I was steering my way home that afternoon to a life that would always include the sea.

Metamorphosis Complete

The last time I saw Sans Souci, more than a decade later, she was making her way up Bay Shore's Penataquit Creek one blue fall day. I was bailing the night's rain from a clam boat I kept there, and I watched the old cruiser slice cleanly through wavelets raised by a north wind. The Judge, wearing a faded canvas coat, was on the bridge with his second son, who would later buy the boat from his dad and live aboard her before moving overseas. They were on their way, I imagine, to a yard further up the creek that would haul Sans Souci for the season, then truck her to The Judge's house, where she'd rest in the shadows of some big pines until spring came again.

Ten years is a long time for any wooden boat, especially one as old as Sans Souci when she and I first met. Her wheelhouse had grown darker — the glow of old brightwork deepened over time — and she had about her that rueful air old wooden boats wear when they can't be driven hard anymore and refastening them just doesn't pay, though sentiment sometimes argues for it anyway.

Life being what it is, my family had bought a cruiser of their own by the time I was 12, and I never sailed on Sans Souci again. Maybe that was a lucky thing. It might be why I remember her better for the magic of that one chance meeting long ago.

The poet Goethe said that the richest life we can live is one focused on those very few things which claim our deepest sensibilities, those which wake the poet in us and render us fully human. For me, these waters I live by have served this aim as well as anything might have. The years have not dulled their wonders, nor lessened their mysteries. Nor have the years dimmed my memories of Sans Souci, and the day she first carried me home over them.