Advertisement

A treasured diary uncovered in a family archive gives us a snapshot of exactly what boating was like a century ago. Sometimes it was very hairy out there!

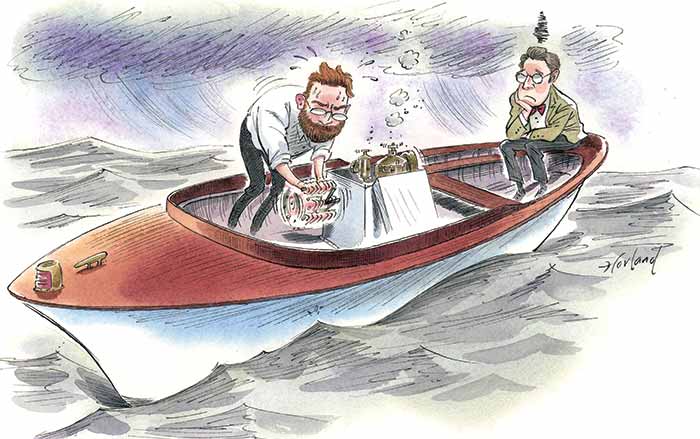

Illustration: Gary Hovland

In this age of modern boats big and small, full-service marinas, reliable navigational aids, VHF, GPS, AIS, TowBoatUS come-to-the rescue support a cellphone call away, it's easy to forget how boating was very different a generation ago. I was captivated to find a rough-and-tumble boating account penned by my great uncle in 1948. This true tale of "the way it was" will resonate with all of us who love boats.

My grandfather, also named Joseph Halsted (I was born on his 80th birthday in 1945 and given his name) purchased 80 acres with a small house for $300 on the north shore of Lake Charlevoix in 1905. Joe was a skilled machinist who owned a decorative-iron foundry in Chicago.

Roads were poor then, so to get from his new home to the town of Charlevoix, he sought better lake transportation than his horse and buggy on a dirt track. The family of five, with many frequent visitors, traveled to this lake house, named "Neatherwood," every summer by steam ship from Chicago.

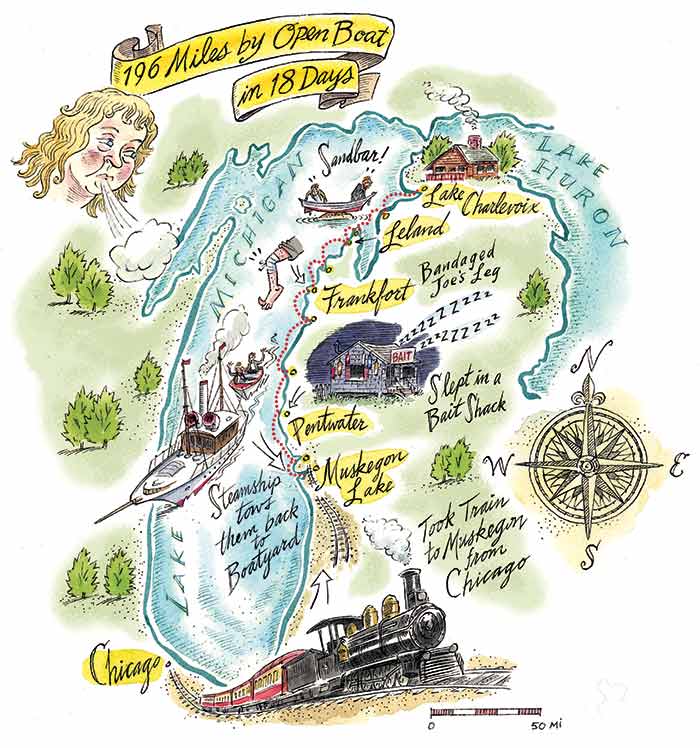

Visiting the Chicago Boat Show in 1910, Joe became intrigued with a 25-foot Gilman Motor Launch powered by a Fairbanks Morse 7-hp motor. He bought it for $559.85 and named it Comet, as Halley's Comet had recently made a close pass by Earth. With his brother-in-law, my great uncle Bill, he decided to set out on what turned out be an arduous voyage from Chicago to Charlevoix. Joe and Bill took a train from Chicago to the Gilman Boatyard in Muskegon, then motored out to Lake Michigan from there.

Illustration: Gary Hovland

Comet was advertised to run at 10 knots but never surpassed 7. Neither Joe nor Bill had ever run an internal-combustion marine engine (neither even owned a car), and this was one of the first marine engines Fairbanks Morse had ever built. All small-boat engines then were far from reliable.

Joe and Bill left the Gilman yard in Muskegon in the just-completed new boat on a warm summer day. Before even clearing the river, the propeller nut came loose. Tying the boat to a tree, they hiked back to Gilman, who came out and made the repair. While waiting, Joe fell into the boat and injured his leg.

The next day, they set out again. Within an hour the steering cables broke and the engine died. A friendly steam yacht came by and towed them back to Muskegon, with Joe steering with a huge wrench on the rudder post, and Bill on the bow holding the towrope in the chock. To restart the engine required laborious cranking of the flywheel by hand. It was sparked by an induction coil producing such a weak charge that the fuel mix had to be exactly right. It would often stall, requiring another laborious spell of cranking the heavy flywheel.

They left Muskegon in the new Comet with no charts, no experience, just plenty of gumption. The prop would fail, then the steering, then the engine ...

On the third try out they got a dozen miles north, close to White Lake, when the crankshaft bearing failed. Limping into Whitehall with the motor howling, they found a mechanic who worked all night and replaced the bearing.

In the morning, heavy seas at Point Sable turned them back. The following day, braving whitecaps, they made more miles before tying to a rickety vacant dock at Pentwater. In heavy rain, they installed the provided canvas boat cover and attempted to sleep on seat cushions, ending up drenched. In the dark they stumbled around the harbor, across railroad tracks, past a canning factory to a bait shack, where the lone occupant offered two dirty pallets on a dry floor on which to sleep. As luck would have it, this was Old Home Week in Pentwater, and the two were fed all they could eat for 25 cents. Weather kept them there for two more days. At first dawn, with the lake a mirror, they set out for Ludington, 15 miles to the north. But before making port, the coil failed completely, leaving them dead in the water. A fishing boat charged them $15 for a tow into town where they found a new coil. The boat then ran well to Manistee, mooring overnight at Onekama and motored past Arcadia to moor again at Frankfort, where Joe got his injured leg properly dressed.

They set off again, passing Empire and almost to Sleeping Bar Point when the new coil started to fail. With only one cylinder firing, they limped Comet back to Empire and trudged through the hills, finding another new workable coil there.

Running past Bear Point in the morning, they looked longingly into Good Harbor, but with a strong northwest wind, the harbor offered no shelter, so they pressed on to Leland. With no chart aboard, they were unaware of the navigational hazards ahead. Barely squeaking over several sandbars, they ran aground on one. Shoving off, they drifted out in the dark and tried again. At full speed the boat bumped the keel over yet another bar before finally making their way into a creek. They tied to a tree for the night, which turned into three, while they waited, tied among fishing boats, all sheltering from a three-day storm.

The fourth morning, they rounded Cathead and crossed Grand Traverse Bay to Norwood, where they rested at an inn, enjoyed a good breakfast, and watched a squall roar across the lake. From there it was around Fisherman's Island, barely avoiding a collision with a floating 20-by-20-foot wooden hatch cover from a large ship, which Joe spied just in time.

There would be injuries, groundings, rescues, storms, and endless hand-cranking. They'd have the time of their lives!

Her use for transportation to town ended in the mid '20s when a paved road was built. The Great Depression curtailed summers in Charlevoix to just a few weeks, and a leaky barn roof one winter filled Comet with water, splitting the seams and rusting the engine. The decayed remains of her bones rest now in the woods behind the nearly buried foundation of the barn.

This century-old account of what boating looked like in our grandparents' generation is a reminder that, no matter the era, the size of our boats, their age, our age, or how well we maintain our beloved craft, stuff happens. Constantly. It always has and always will. But it's the journey that counts in the end, and that they — and we — never tired of setting out, hoping for the best, and seeing where their boats took them.