Advertisement

Advice on getting your partner to love boating as much as you do.

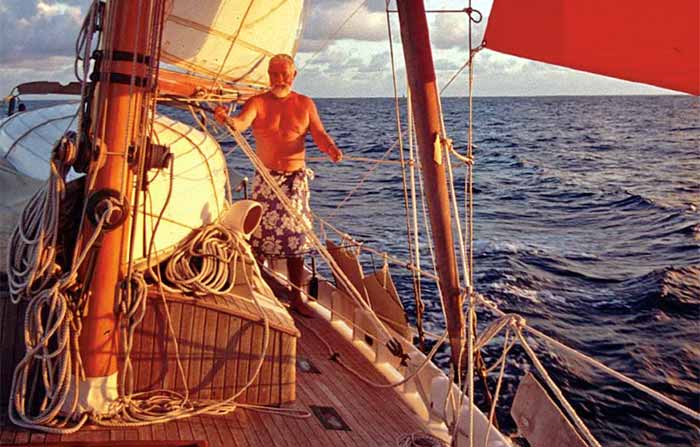

Photo: Onne Van der Wal

A warm, caressing breeze soothed the northwest swells as Larry urged me to try my hand at Agamemnon's wheel. It was my first time being more than 20 miles from shore. Larry and I had known each other for six months, and I'd been asking him to take me along when he delivered boats. Until this peaceful night, he'd made excuses, limiting my experiences to afternoons on friends' boats, or in the dinghy. Now, as we shared a beautiful midnight watch, I stared at a star instead of constantly staring at the compass, and waxed poetical about the moment. Larry put his arm around me and said, "An old friend told me, you'll go out 10 times before it happens — that perfect boating experience — and you'll keep going out nine times more to recapture that magic."

Make cruising a real pleasure by getting off the boat to savor shore pleasures. (Photo: Michael Marris}

It was a half-dozen years of loving the boating life before I learned how carefully he'd planned my introduction to it. Boating and cruising may be the dream of only one member of a couple. The following are ideas on how to encourage your partner, and make the dream as much theirs as it is yours.

Introduce your partner to boating gently.

It starts with those first experiences. If you're experienced yourself, go out of your way to plan each boating day so your partner gradually builds confidence in your skills and at the same time gains his/her own confidence. If both of you are new to boating, make sure your early excursions build confidence. Go out in only beautiful, calm weather. Ask around until you find other boaters known to be competent and relaxed. Invite them to go with you. If you hit it off, they might invite you out on their boats so you and your partner gain knowledge about best practices and using gear more successfully.

Don't fool yourself by thinking that it's easy to become a successful skipper. Look at it from your partner's perspective. Would you fly across the Atlantic with someone who just got his or her license to fly a plane? It's easy to buy a boat and learn the basics of maneuvering it. But it takes time and varied experiences to become proficient so you react correctly and calmly in a variety of situations. If you take the time to learn and practice before attempting anything ambitious, you'll avoid confidence-sapping situations that could destroy your dream of boating with your partner.

Don't promise that cruising will be perfect. Yes, there will be days when dolphin guide you across sunlit seas. This was taken as we headed toward Kiritimati in the Line Islands south of Hawaii.

Remember, everyone really IS watching you.

The knowledge that hundreds of eyes are on you as you come into the marina creates concerns and tension that can turn you from a relaxed, coming-home-to-roost boater, to a matador about to be gored by a raging piling. Your voice rises; your partner's hackles rise in response. Anger creates inattention, which leads to fumbles that escalate the problem — one more chip in the confidence you should be building in your partner.

Until you've both gained confidence, avoid entering marinas during peak hours. If possible, anchor out in clear water until after the rush, or until the wind eases. If you're planning to anchor, forget trying to find a spot close to shore, where it's crowded. Anchor farther out, even if it means a longer dinghy ride ashore. Then find some time during the week when fewer eyes will be around and practice docking, anchoring, and mooring procedures without spectator pressures. Create communications plans. Figure out ways to make your boat easier to handle in marinas, such as clearing the side decks and adding easier-to-reach handholds to help you or your partner climb out of the cockpit more quickly. Consider adding rub rails with brass half-round strapping to protect the topsides. But above all, discuss and accept the pressures that observers create.

Women, please take note: Our vanity is more often wrapped up in the physical appearance of things — i.e., is the boat clean and well organized? Men's vanity tends to be more wrapped up in how their actions appear — i.e., did I look like I knew what I was doing when we came in? Accepting these differences will help during those times when spectators, and the pressures they add, are unavoidable.

Candidly discuss the fear yelling creates and the power it gives.

True story: It was a race day and 25-knot winds were forecast. I was slated to skipper a Buzzards Bay 25, a boat I'd sailed twice in light winds. This was a big regatta right on the waterfront. My all-female crew consisted of two neophytes and a foredeck hand who'd never sailed this kind of boat. We invited Larry to join us on the condition that he "act like a lady."

"Spell it out," he joked. "What are the details?"

"Rule one: We're out here to have fun," said Sarah, the boat owner. "If anyone makes a mistake, no blaming her. We're all in it together. Rule two: No yelling."

The rest of my crew added, "Rule three: No yelling." Halfway up the windward leg, we passed yet another boat, and began to feel very competitive. Sarah called out, "Larry, yell when you're ready to tack. You almost wiped us off the cabin top."

Larry retorted, "Can't yell, I'm being a lady."

Advertisement

We all called back in almost perfect unison: "Forget that! Yell so we can hear you!" It became a standing joke for the three days of the regatta. "Don't be a lady, yell," we called to our foredeck hand when we couldn't hear her commentary on which boats were tacking ahead of us. We'd learned several lessons. Men learn at an early age that yelling is part of the aggressive team sports they play, a way to be sure their teammates hear them above the fray, noise to be forgotten the minute the game is over. Most women are raised to feel that yelling is reserved for times of anger or fear. The memory of raised voices lingers in a woman's mind long after the incident has passed.

Talk together about this scenario: You're coming in to anchor, the wind gusting 25, engine thumping, a dodger between you at the helm and your partner on the foredeck 30 feet from you. Your partner is, by necessity, facing away from you. How can you make sure he or she hears you, without yelling? Practice helps. Developing hand signals and wearing two-way radio headsets help some couples. Lowering the dodger, adding more sound insulation to the engine room — all helpful. But what we found works best is practicing calling "very loudly" and then having the other person repeat the order so that each person knows the other heard and understood. Finally, be ready to accept that some instances of yelling are caused by your own tension/apprehension, real or imagined. Apologize sincerely once the situation is under control and explain that no anger was intended so you can work toward developing into a better boating team.

Give your partner (and yourself) room to make mistakes.

No one does their best when someone is coaching them constantly. In fact, as Larry and I have relearned several times, the more he coaches me, the more my helming skills deteriorate. I begin to pay more attention to what he might criticize than I do to steering. He's trying to keep me from making the mistakes he made as a novice. But, as I remind him, he was able to learn by making those mistakes. Now it's my turn. Not an easy thing for men to accept. That's why I recommend that women attend one of those all-female boating courses, which gives them a chance to gain confidence and hone skills in a conducive and less threatening atmosphere.

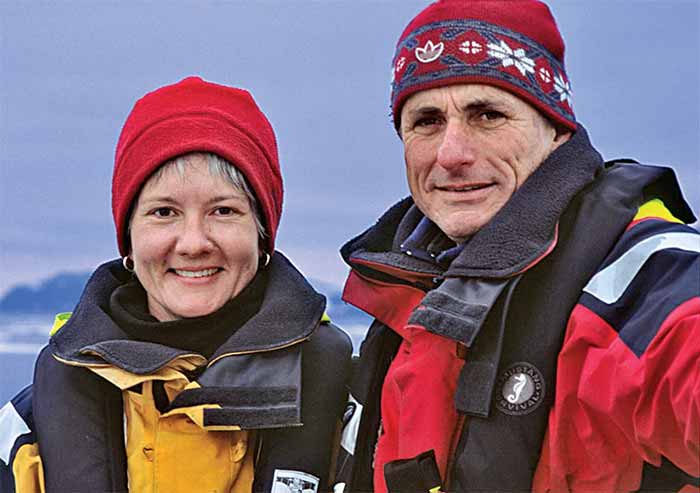

Don't suggest overly adventuresome sailing destinations until she fully embraces your dream. John Harries and Phyllis Nickel did not take Morgan's Cloud to Iceland until they had acquired a lot of sea time in more moderate climates. (Photo: Lin Pardey)

On the other side of the coin, by allowing for mistakes without letting it ruin your day, you'll also make life afloat more pleasant for your partner. Boats are pretty tough machines. If you avoid $10,000 spray-on topside paint and highly varnished toe rails, a chip caused by a misjudged dock approach becomes "just a little putty, a little paint, no big deal." Boats are far easier to mend than broken relationships.

Don't make false promises about boating.

Boating isn't always easy, and isn't always romantic. Say it is and you're leading yourself astray, too. Furthermore, even the most sumptuous 45- or 50-footer will never have the space or convenience of a small apartment on shore. So don't lure your partner afloat on the premise that it will be more comfortable. Boating is physical. You must carry everything you use from the shore to the boat. You have to store things so they don't get loose in a seaway. This means you'll always need to move one thing to get something else, which is a hassle. When you actually set off on a cruise, learn to give each other physical and mental space. Be realistic, and talk about it more as an intimate adventure that will connect you to nature.

Make and keep real promises about what boating can offer.

Think beyond the boat when you're trying to entice your partner into the boating life. Imagine what she loves to do, and incorporate those interests into your time on the water. Does she love craft shows, antiquing, or art galleries? Then dinghy ashore and stroll the shops with her in new towns you visit. Does she love visiting historical sites? Make time for that. Does she love biking, walking on the beach, dining out? You know what you have to do. Before you know it, your partner will connect boating with her interests, and view the boat as a vehicle that opens her to new experiences that she loves.

Contingency planning calms fears.

The majority of women I know don't know how to troubleshoot or fix diesel engines, generators, or electrical systems. Some have never operated the VHF radio. One fear that eats away at some women is how they'd bring the boat home should the engine and electronic gear give out, or something happens to the skipper. Some boating schools now offer courses on how to bring your boat back into port alone, anchor, then contact assistance should a partner be out of commission. Women do worry about this scenario. Address it together and you'll have removed one more obstacle to boating.

Encourage your partner to talk to other experienced women.

There's nothing as contagious as enthusiasm. Include as many positive-reinforcement opportunities as you can. Conversely, especially at the beginning, try to minimize or short-circuit encounters with people, lectures, books, and movies that emphasize the negative aspects of boating.

Create an exit strategy.

Once, when we were facing an upwind slog of about six days, I felt my confidence sapping away. Larry encouraged me: "Let's go as far as Portobelo. It's only 20 miles to windward. If you really hate it, we'll come back and I'll find crew to help me sail up, and meet you at the end." That worked. I had an out. I tried it his way and learned my fears were grounded in inexperience. I didn't love bashing to windward for six days, but I did enjoy the accomplishment.

Be logical about boat maintenance.

My friend Lori Lawson interviewed 27 boating couples and asked what they liked least. Maintenance topped the list. If it isn't a problem with the refrigeration, it's the generator, watermaker, or radio gear. Simplicity is one way to cut down on maintenance. A modest-sized boat helps. Learning to inspect gear and avoid breakdowns in advance helps. Once you leave the dock, it's 10 times harder to fix gear, because it's up to you to do it. In Lori's survey results, the top four ways that couples found to create a successful boating partnership were: establishing a sense of interdependence; sharing the same boating goals; trusting each other when the going got rough; and establishing good communication methods. Communications are the key to good boating partnerships. Combine learning how to communicate afloat with some confidence-building boating experiences, and you'll increase your partner's enjoyment and sense of self-sufficiency.

The Little Things That Help Partners Build Confidence

Photo: Lin Pardey

- Print out clear step-by-step procedures for using the radio, head, and engine; laminate each one; and affix them near each apparatus. Knowing how to use these marine devices builds confidence in new boaters — and in your guests.

- Buy a waterproof hand-held VHF that either of you can take with you in the dinghy. Cell phones aren't reliable enough in the marine environment, where reception may be spotty.

- Develop and practice hand signals for: go left, go right, go forward, stop, reverse, increase RPMs (the latter to be used when backing down on the anchor). Then, if your partner can't hear you above the wind, you have a calm, no-stress way to communicate.

- Arrange your main anchor and its rode so it's easy for your partner to release and use in an emergency situation.

- Make sure your tender can be easily launched by your partner alone, and that the oars and outboard are fully tested and ready to use.

- Despite how big your boat is, when you go on the foredeck when it's rough, or after dusk, or before dawn, always wear a life jacket. Your partner will breathe a sigh of relief.

- Add a grab-it hook to your boat-hook to help you and your partner attach lines to a mooring, or to a dock cleat.