Advertisement

When you need to make a call for help, you want to be 100 percent certain that call will go through.

Photo Credit: U.S. Coast Guard

In the middle of the summer of 1899, the barkentine Priscilla foundered on the shoals off North Carolina's Outer Banks. With no way to call for help, the 10 men onboard were in imminent danger, but luckily, a beach patrol on horseback from the Gull Shoal Lifesaving Station spotted the wreck — and all hands were saved. Flash forward to the winter of 2012. The 48-foot sailboat Wolfhound loses all power and spins out of control in 50-knot winds and 20-foot seas. But this takes place a solid 680 miles east of where the Priscilla met her fate, and there's zero chance of a lucky encounter with horseback-riding rescuers. Someone onboard the Wolfhound presses a button. Moments later the Coast Guard Fifth District Command Center in Portsmouth, Virginia, receives the signal from an emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB). Within hours an HC-130 Hercules based in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, is circling above the stricken sailboat. As with the Priscilla, all of the people onboard are saved.

Separated by 115 years of technology, the only things these two cases share in common is that both vessels were in imminent danger, and both crew were successfully rescued. One thanks to sheer luck, and the other thanks to modern electronics.

The EPIRB is not, of course, a completely new development. In fact, EPIRBs have over 22,000 rescues to their credit. Having been in use for over three decades, however, today's EPIRBs are significantly advanced over those of yesteryear. And just as importantly, the concept of sending a signal through the air to call for help has been thoroughly expanded upon. Now, you can send out an SOS with a wide variety of devices including cell and satellite phones, satellite text messengers, and PLBs (personal locator beacons). With choice comes the need for informed decision-making. And correctly deciding which of these systems is best for you is only possible with all the facts in hand. Here are your choices, and the pros and cons of each.

Cell Phone

The Pros

Your cell phone is, without question, one of the easiest and most effective search and rescue (SAR) devices of modern times. With it you can speak directly to SAR personnel, give them position and situational information, and receive instructions. Modern smartphones can also provide you with GPS data and backup navigational abilities. And if you need your hands free to keep your boat afloat or render medical assistance to a passenger, you can activate an application like the SARApp or ICE. And don't forget the BoatUS towing app, which sends your position directly to the BoatUS dispatch center.

The Cons

Unfortunately, cell phones remain one of the least reliable forms of communications on the water. Range is obviously limited. Even if you always boat within sight of land, they simply can't be depended upon to get a signal, especially in life-or-death situations. Their batteries always seem to run out when we need them the most. On top of that, the Coast Guard specifically requests that SAR contacts not be made via email, which is how some of the cell phone emergency apps are set up to work. Finally, consider how vulnerable cell phones are to water damage. And unlike on a VHF radio, there's no way to put out a general call to anyone within hearing range. Even though it may be the first thing you reach for in case of emergency, you simply must never rely upon a cell phone as your primary form of signaling for help.

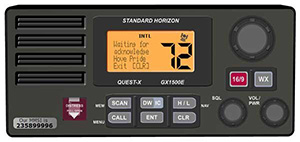

VHF Radio With DSC

The Pros

The VHF radio is just about the most common form of emergency marine communications around, and with good reason: It's simple to operate, communications go both ways, and, with a properly installed DSC (digital selective calling) radio, when you hit the panic button, the USCG will automatically get your exact GPS position, they'll know you're sending a distress call, and they'll know who you are. VHFs are also relatively inexpensive, easy to install, and virtually all of the models on the market today are rugged and reliable.

The Cons

The biggest downfall of VHF with DSC is the same as it is for all VHF radios: Your range is limited by the curvature of the Earth. Antenna height plays a big role here, as can atmospheric conditions. With an average fixed-mounted antenna on an average pleasure boat, you can't expect a range much over 20 miles. Also, the fixed-mounted VHF on your boat probably depends upon your boat's electrical system for power. If you're adrift with dead batteries, the radio won't help one iota. Carrying a backup handheld unit with its own power source is always a good idea, but these units have even less range, sometimes as little as a mile or two. Finally, if you have a DSC-capable VHF, you need to make sure it's properly interfaced with your GPS to give position data — something the Coast Guard estimates eight out of 10 boaters fail to do — and it needs to be registered with a Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) number. MMSIs for domestic use can be obtained from BoatUS.

EPIRB

The Pros

Thanks to a proven track record of high reliability, EPIRBs remain a top choice for sending out an emergency signal to SAR personnel today. Since EPIRBs interface with Cospas-Sarsat international SAR (search and rescue) satellites that calculate your position via GPS, triangulation, or a combination of the two, they are essentially unlimited in range. EPIRBs are also equipped with a strobe light for quick visual acquisition, can be activated either manually or automatically, are required to float and be completely waterproof, and can be mounted with hydrostatic releases.

The Cons

Despite excellent reliability and a long history of saving lives, if the EPIRB were perfect, it wouldn't have all of this competition. First, consider expense. Bottom-of-the-line models cost over $500, and high-end units cost over $1,000. And it's not a one-time cost, since EPIRB batteries usually need to be serviced by the manufacturer as they age, about every five years. Less expensive units commonly aren't GPS-equipped, which expands the effective search radius from a few hundred feet to two nautical miles. And EPIRBs cannot be taken from vessel to vessel. They must be registered to a specific vessel, so you can't legitimately use one unit for multiple boats. But an EPIRB's biggest downfall may be its limited communication ability; it can send out a cry for help with your location information and vessel data, but that's it. They don't receive any form of communications, and they don't have the flexibility to transmit any additional data. You can't discuss emergency repairs procedures, medical treatment, or any of the other matters that could make the difference between life and death in an emergency situation.

PLB

The Pros

A personal locator beacon (PLB) is much like an EPIRB, in that it sends out an automated distress signal to the Cospas-Sarsat satellites with an essentially unlimited range; GPS, triangulation, or both are used to nail down your position. They're also smaller than EPIRBs, less expensive (some can be purchased for less than $300), and completely portable. They are small enough to be carried by crewmembers at all times, and they have been used to locate crew in overboard situations.

The Cons

On the surface it may seem that a PLB is a better choice than an EPIRB until you consider the downsides of depending on these units. For starters, they have half the guaranteed battery life. Not all units have strobes (though many do) and all require manual activation. Finally, not only do they suffer from the same limited-data constraints of the EPIRB, rescuers may actually receive less data because boat information is not required for registration.

Satellite Messengers

The Pros

Satellite Messengers are a relatively new development, with the first (the SPOT) being introduced about five years ago. But they've developed rapidly since then, with expanded capabilities. Text messengers use satellite communications to bounce a short text message to an individual party or, in times of need, to emergency responders. When you hit the SOS button, these transmissions include your exact GPS position in the data feed. These units are extremely small (the size of a cell phone or smaller), inexpensive (some can be had for as little as $120), rugged and waterproof, and are easy to operate. Some allow for two-way communications via an integrated keyboard, some use Bluetooth to pair with a cell phone and allow two-way texting, and some allow only one-way texting of pre-typed messages. They run on either store-bought lithium or rechargeable internal batteries, and while operating times vary, can generally send out their messages for days at a time.

The Cons

Satellite Messengers use commercial networks rather than the Cospas-Sarsat system, so they charge for airtime and are sold with a monthly or yearly service contract (ranging from about $100 to $500 per year depending on service level). Your SOS transmission does not go directly to the USCG but to the GEOS Emergency Response Coordination Center, which then ascertains the proper SAR agency to contact. The GEOS track record is good — they've assisted in the rescue of over 3,500 people in the past five years — but this does add another step into the emergency-response process. Also, the different units' capabilities vary widely depending on the type of unit and service you choose. While some allow for two-way communications, others can only transmit, not receive. And in some cases, they can only transmit a distress signal.

HF Radio

The Pros

For those planning to spend a lot of time out of cell phone and VHF range, HF (High Frequency) radios — single sideband (SSB) or ham — provide two-way, long-distance communications and can be used to contact rescuers directly. HF signals can be transmitted for hundreds of miles, and in the right conditions can span entire oceans. Newer DSC-equipped models offer the same push-button emergency signaling and retransmission of distress signals from radio to radio as DSC VHFs. HF radios are like party lines — which means that someone will hear you in an emergency even if it's not the party you were attempting to reach, and they can then relay the message to rescuers.

The Cons

Ham radios cost about $800, but they are dependent upon good antenna systems and ground planes to perform well so the installed cost will easily be double that. A simple test is required to operate a ham radio. No test is required to operate an SSB, but marine SSBs are much more expensive, starting around $1,500 with an installed cost of $3,000 or more. Transmission quality is dependent on atmospheric conditions, and there may be times when it is all but impossible to get clear communications with the desired party. Finally, these radios consume a fair amount of power so if your ship's batteries go down, the radio goes down with them.

Satellite Phone

The Pros

For fast two-way communications without any limitations on the information that can be conveyed between rescuer and rescuee, a sat phone is going to be tough to beat. It allows you to speak firsthand with SAR personnel, continually, from virtually any place on the planet. As well as relaying location and emergency information, you can communicate medical situations (and receive instructions from special-knowledge responders) and any other pertinent info. You can contact parties outside the SAR system. Marine models are rugged and waterproof. Both portable and fixed-mount units are available, as are extra batteries. That means you could take the portable with you if you have to abandon ship.

The Cons

Unfortunately, satellite phones are not cheap. Most brands start at around $1,000 (though at least one model new to the market this year has an MSRP of $500) and can cost several thousand dollars. Worse, they get a lot more expensive if you actually use them. You may have to buy a monthly plan and with many of them, you'll also have to pay $1 or more per minute of use. Plus, the Coast Guard doesn't have a 1-800-RESCUE-ME number to call. Different areas are covered by different regional Rescue Coordination Centers, each of which has its own emergency line. It's not hard to find these numbers and preprogram them into the phone but in any case a sat phone doesn't create an idiot-proof direct link of units like EPIRBs and PLBs. Finally, most portable sat phones have a fairly limited battery life and talk time, which may span just a few hours.