Advertisement

Finding fault can be tricky at sea. The bottom line is to be conservative; take evasive action, even if you think you're in the right. Here's why.

With some collisions, fault is obvious, like the collision that occurred when the skipper of a 45-foot powerboat in Florida slammed into the stern of a 31-foot boat late one night in a narrow waterway. The skipper of the larger boat had been drinking heavily and his boat was traveling at almost 50 mph, over twice the posted speed limit.

But with many collisions, perhaps most collisions, assessing liability isn't so easy. Last summer, for example, a small fishing boat and a trawler collided on a clear day on the Chesapeake Bay after having each other in sight for almost 10 minutes. Seas were calm and the open stretch of water near the mouth of the Potomac River was remarkably free of other boat traffic. The first boat, a 26-foot center-console, was heading north, off Smith Point Light, and its skipper said later that he thought his boat was moving faster and would pass in front of the trawler. He admitted that his attention was focused elsewhere.

The second boat, the trawler, was headed northwest toward the Potomac River. The trawler's skipper said that he was well aware of the smaller boat but his boat had the right of way and he held his course until a few seconds before the collision — far too late to move out of harm's way.

Liability Of The Stand-On Vessel

For many years, the Rules Of The Road made a distinction between "privileged" vessels and "burdened" vessels in meeting, overtaking, and crossing situations. The two terms were eventually abandoned because they're misleading. The Rules are not intended to establish guilt in the event of a collision, as these older terms seemed to suggest; both vessels have a responsibility to avoid a collision. The terms used today, "stand-on" and "give-way," indicate the course of action that each boat is intended to follow. If the skipper of the give-way vessel doesn't appear to know the Rules or isn't keeping a proper lookout, it's up to the skipper of the stand-on vessel to take the necessary steps to prevent a collision. That's also in the Rules, Rule 17 (b), which says, "When, from any cause, the vessel required to keep her course and speed finds herself so close that collision cannot be avoided by the action of the give-way vessel alone, shall take such action as will best aid to avoid collision." Rule 17-b is the ultimate rule, if you consider that it is the last rule to be applied before an impending collision.

Sooner or later, every skipper will approach another boat whose skipper either doesn't know the Rules Of The Road or isn't keeping a proper lookout. When the two boats collided on Chesapeake Bay, the skipper of the center console — the give-way vessel — didn't give way because he wasn't keeping a proper lookout (Rule 5). That does not make him solely liable for the collision, however.

Farwell's Rules Of The Road states that: "It [Rule 5] is not meant to imply that whenever two vessels collide, that mere proof of improper lookout on either vessel, in the technical sense, will ipso facto condemn that vessel for the collision. On the contrary, it has been held by the Supreme Court that the absence of a lookout is unimportant where the approaching vessel was seen long before the collision occurred."

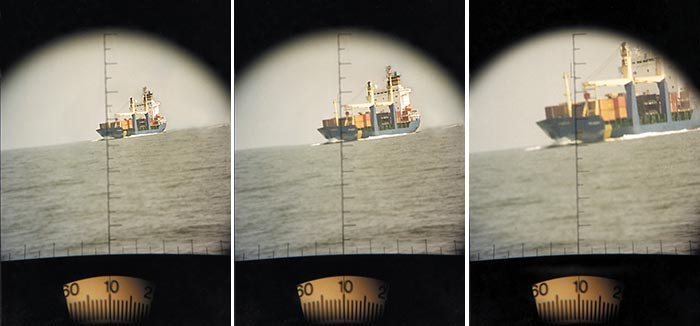

As you watch through binoculars, if the bearing of an approaching boat remains the same, you are on a collision course. (Photos: Bob Adriance)

Besides turning to avoid the collision, the skipper of the stand-on vessel could easily have slowed down or stopped, which would've allowed the give-way vessel time to pass safely in front of his boat. One of the more serious collisions in the claim files involved a runabout that was cruising on the port side of a waterway heading north (the wrong side) and met another boat at a sharp bend heading south. Both boats made a quick series of offsetting maneuvers before finally colliding head on. Although the investigating officer noted that the northbound boat was cruising on the wrong side of the channel, both skippers were cited for failure to slow their boats before the collision.

Some Exceptions To Shared Liability

There are situations where liability is less likely to be shared. An overtaking vessel (more than 22.5˚ abaft the other vessel's beam) that runs into the stern of a boat, according to Farwell's "is solely [emphasis added] liable as long as the vessel being overtaken maintains her course and speed as required under the Rules."

If a vessel comes up relatively close to another vessel from any direction more than 22.5˚ abaft the latter's starboard beam, draws ahead, and subsequently turns to port to come onto a crossing course, Farwell's says that the overtaking vessel would not be relieved of her duty to keep clear and notes that the courts have found that this applies not only in restricted waters, but wherever an attempt to pass might mean risk of collision.

The Rules also take into account the lack of maneuverability of large ships and you can't expect to cruise down the middle of the shipping channel and get off lightly in court using some David and Goliath, "I'm just a little boat," defense if there's a collision (assuming you survive the collision). Quite the contrary, Rule 9d is very specific: "A vessel less than 66 feet in length or a sailing vessel shall not impede passage of larger vessels that can safely navigate only within a narrow channel or fairway." It's a rule that the Coast Guard takes very seriously. A ship's pilot was preparing to pass a large tug and barge at night in Delaware Bay's shipping channel when a sailboat ahead failed to tack and instead maintained its course across the ship's bow. The pilot sounded five horn blasts (danger), which only seemed to confuse the sailboat's skipper. The sailboat skipper held his course and the pilot was forced to turn the ship, which collided with the tug, inflicting a total of $377,000 worth of damage to the two vessels. The Coast Guard located the sailboat's skipper later that night and held him completely liable for the damage. It is worth noting that the sailboat's skipper only had $100,000 worth of liability coverage, which meant that he was personally responsible for the remaining $277,000!

Advertisement

Avoiding Collisions: A Practical Approach

From the surveyor's report from yet another claim: "Officer Figular related that the initial cause of the accident was [the other skipper's] failure to give way. He said she turned to port and the [skipper of the stand-on vessel] responded at the same instant by turning to starboard. Officer Figular said both boats were cited because neither vessel backed off of the throttle in an attempt to avoid the collision."

In any crossing situations, the best way for the skipper of the give-way vessel to avoid frantic last-minute maneuvering, which creates confusion and increases the likelihood of a collision, is to make course changes early, and the sooner the better. (See below "The Art Of Taking Bearings".) At a mile or two, a slight change of course will usually suffice, but the closer the two boats are the more important it becomes to make a course change that will be immediately obvious to the other skipper. One tactic is to head for the other boat's wake until you're certain it's going to pass safely in front of your boat.

The Art of Taking Bearings, And Surviving A Crossing Situation

Two explanations that are often given in collision claims that we see at BoatUS Marine Insurance: "Uh, I thought he was going to pass in front," and "I thought he would pass astern," both of which indicate that the skipper didn't have a clue how to take bearings or for that matter how to avoid a collision. Let's fix that right here, right now.

Even if you're an experienced skipper, it's not hard to occasionally misjudge the speed of another boat, especially when it's still a safe distance away. Rather than make a series of last-second maneuvers, which don't always work, you can use a hand-bearing compass or binoculars with a hand-bearing compass to asses the risk of collision. If your boat's speed and heading are constant and the compass bearings are moving forward, the other boat should pass ahead. If the bearings are moving aft, the other boat should pass astern. The farther the bearings move, the farther away the two boats should be when they cross. A series of bearings that remain constant, or nearly constant, indicate that the two boats are converging on a collision course. More experienced skippers have learned to choose a convenient object on the boat, such as a stanchion or a winch, that lines up with the approaching vessel; if it remains in line with the reference object, the two vessels are on a collision course.

Don't take chances. When in doubt, if yours is the give-way vessel, head for the other boat's stern. If yours is the stand-on vessel, be prepared to alter course anyway, lest the skipper on the give-way vessel takes the "Uh, I thought we were going to pass ... approach to avoiding collisions.

What if you're the stand-on vessel and the other skipper either doesn't understand the Rules or doesn't see you? Five or more short blasts, signaling danger, should get his or her attention. If not, slow the boat immediately and turn away from the collision. DON'T wait until the boats are a few yards apart to take evasive action; the longer you wait, the more radical your maneuver will be and the more likely the other skipper will become confused.

When approaching another boat head on, both boats are supposed to turn to starboard — Rule 14(a) — to avoid a collision. The turn must be obvious, so that the other skipper clearly sees your boat's port side. In a crowded channel or fairway, boats should keep to the right side of the channel, just like on a highway.

Besides crossing and approaching, the other situation addressed by the Navigation Rules is overtaking. When you're approaching another boat from astern, sound one short blast if you'll be overtaking on its starboard side and two if you'll be overtaking on its port side. While you can't be sure your signals have been understood, signaling has the advantage in any situation of getting the other skipper's attention. (If you respond to another vessel's signal, respond with the same signal or the danger signal — never respond with a contradictory signal.) You can also try contacting the boat's skipper on your VHF. The overtaking boat will be the give-way vessel, even if it passes to the right and moves into the other boat's danger zone. Finally, to save aggravation and possible injury, both boats should slow way down to reduce the size of their wakes until the overtaking boat is safely clear.

Are You On A Collision Course?

The skipper of a 27-foot sailboat that was motor sailing across Lake Michigan flipped on his autopilot and went below to check his charts. After a few minutes the sailboat's skipper poked his head out of the hatch and saw a large fishing trawler several miles away that seemed to be moving very slowly. He watched it for several minutes and then — a big mistake — went back to his chart, convinced the trawler would pass well astern of his boat. It didn't. In what the sailboat skipper described as "a very short amount of time," he heard a series of loud whistles, but it was too late to avoid a violent collision with the tug.

It's easy to misjudge the speed of another boat at great distances. Rather than wait until the last minute, you can use a hand-bearing compass (or the boat's compass) to assess the risk of collision. If your boat's speed and heading are constant and the compass bearings are moving forward, the other boat should pass ahead. If the bearings are moving aft, the other boat should pass astern. The further the bearings move, the further away the two boats should be when they cross. A series of bearings that remain constant, however, indicate that the two boats are converging on a collision course and you must take the appropriate action to avoid a collision.

You can also assess the risk of collision with another boat by lining it up with an object on land. For example, if there is a water tower on land that appears to be moving astern of the other boat, the boat should safely cross your bow. If the water tower appears to be moving ahead of the approaching boat, your boat is moving faster and you should cross ahead of the other boat. If the water tower remains in the same position relative to the other boat, you are likely on a collision course and you must take the appropriate action to avoid a collision. Note that the technique doesn't work when the two boats are converging on a parallel course.